Why Most Product Reviews Have Zero Value for Real Decision Making

The modern consumer faces an absurd paradox: more product reviews exist than ever before, yet making informed purchasing decisions has never been harder. Search for any product and you’ll find dozens of reviews, hundreds of ratings, thousands of comments. The information abundance should enable confident decisions. Instead, it produces paralysis, confusion, and often worse choices than uninformed intuition would yield.

I recently spent three hours researching a cat water fountain for Mochi, my British lilac cat. The review landscape was typical: dozens of “best cat water fountain” listicles, hundreds of Amazon reviews ranging from one to five stars, countless YouTube videos with suspiciously similar talking points, and forum discussions that devolved into arguments about filtration systems. After those three hours, I knew less than when I started. The contradictions canceled each other out. The confident recommendations conflicted. The objective truth about cat water fountains remained as elusive as Mochi herself when it’s time for nail trimming.

This experience isn’t unique to cat accessories. It’s the standard experience across product categories: electronics, appliances, software, services, anything that can be purchased and reviewed. The review ecosystem has grown vast while its utility has diminished. More content, less value. More opinions, less clarity.

This article examines why most product reviews fail to serve their ostensible purpose—helping people make better purchasing decisions. The problems are structural, not individual. They emerge from incentive systems, platform dynamics, and fundamental mismatches between what reviews measure and what buyers need to know. Understanding these problems is the first step toward extracting actual value from the review landscape.

The goal isn’t cynicism about all reviews. Useful information exists, buried within the noise. The goal is developing the critical skills to identify it, the frameworks to evaluate it, and the efficiency to find it without losing hours to content that generates clicks without generating insight.

Your purchasing decisions deserve better than what most reviews provide. Let’s understand why they fail and what might actually help.

The Affiliate Corruption Problem

The most obvious problem with product reviews is also the most pervasive: affiliate marketing has corrupted the entire ecosystem. Most review content exists not to inform consumers but to generate affiliate commission for publishers.

The economics are straightforward. A website publishes “Best X of 2026.” The article ranks in search results. Readers click through to purchase. The website receives a commission—typically 3-10% of the sale price. The incentive is to generate clicks, not to provide accurate information.

This incentive structure produces predictable distortions. Reviews favor products with higher commissions over better products. Reviews favor products that are available for purchase over products that might be better but don’t have affiliate programs. Reviews favor expensive products over cheaper alternatives because the commission percentage yields more dollars.

The “best X” format itself reveals the corruption. Why do these articles always recommend products rather than advising against purchase entirely? Because “you don’t need this product” generates zero commission. Every “best of” article has a financial interest in convincing you to buy something.

The corruption extends to seemingly objective elements. The comparison tables that appear authoritative? They emphasize features that differentiate products the publisher wants to sell. The scoring systems? Calibrated to produce rankings that favor affiliate-friendly products. The “editor’s choice” badges? Awarded to products with the best commercial arrangements, not the best user experiences.

Some publishers disclose affiliate relationships. This transparency is legally required in many jurisdictions and ethically appropriate everywhere. But disclosure doesn’t eliminate bias—it merely acknowledges it. The reviewer saying “I may earn commission if you buy through my link” still has every incentive to recommend products that generate commission.

The scale of this corruption is difficult to overstate. Search for any product category and the first page of results is dominated by affiliate content. The organic, non-commercial perspective has been drowned out by financially motivated content. The consumer seeking unbiased information must wade through an ocean of bias to find any island of objectivity.

Mochi, naturally, was unaware of these dynamics as I researched her water fountain. She remained focused on her core concerns: when is dinner, why isn’t dinner now, and will there be treats after dinner. Her decision-making framework, while limited, at least avoids affiliate corruption.

The Context Mismatch Problem

Even setting aside financial bias, reviews suffer from a fundamental context mismatch: the reviewer’s context rarely matches the reader’s context. A review describes how a product performed for one person in one situation. The reader needs to know how it will perform for them in their situation.

Consider laptop reviews. The reviewer—typically a tech journalist—uses the laptop for a week, runs benchmarks, tests features, and writes an assessment. This assessment reflects the experience of a tech journalist using a laptop for a week. It doesn’t reflect the experience of a software developer using the same laptop daily for three years, or a student using it for note-taking and essays, or a retiree using it for email and web browsing.

The contexts differ in obvious ways: use case, duration, expectations, technical sophistication. They differ in subtle ways too: environment, peripheral setups, software preferences, tolerance for various trade-offs. The review’s conclusion—“great laptop, highly recommended”—assumes context transfer that usually doesn’t hold.

This mismatch is unavoidable in traditional review formats. The reviewer can’t test every use case. The review can’t address every reader’s situation. The information provided is necessarily partial and contextually bound.

The problem intensifies with complex products. A camera system might excel for portrait photography and disappoint for wildlife photography. A project management tool might work brilliantly for small teams and collapse for enterprises. A kitchen appliance might perform perfectly for someone who cooks daily and gather dust for someone who cooks weekly. The review that declares the product “excellent” or “terrible” provides no guidance for readers whose contexts differ from the reviewer’s.

User reviews on platforms like Amazon theoretically address this through aggregation—thousands of perspectives should reveal patterns applicable to diverse contexts. But these reviews suffer their own problems, which we’ll address shortly. And even aggregated, they rarely provide the contextual detail needed to answer “will this work for my specific situation?”

The Temporal Decay Problem

Reviews capture a moment. Products exist over time. This temporal mismatch makes many reviews obsolete before readers encounter them.

Products change after reviews publish. Software updates alter functionality. Firmware patches fix problems (or introduce them). Manufacturing runs vary in quality. The laptop reviewed in January may be meaningfully different from the laptop sold in July, yet the January review appears prominently in July search results.

Services change even more dramatically. The streaming service reviewed last year has different content, different pricing, different features. The cloud platform reviewed six months ago has updated its interface, changed its pricing tiers, deprecated APIs. The review describes a product that no longer exists in the described form.

Some review publications update articles periodically. “Updated January 2026” appears at the top, suggesting current information. But these updates are often superficial—a sentence changed here, a specification updated there. The core assessment, based on testing that may be years old, remains unchanged. The “updated” label provides false confidence in currency.

The temporal problem extends to context changes beyond the product itself. Market conditions shift—what was the best option two years ago faces new competitors today. Use cases evolve—features that seemed important in 2024 may be irrelevant in 2026. Price points change—the value assessment depends on pricing that fluctuates constantly.

Reviews also can’t capture product longevity. The reviewer tests for a week; the reader owns for years. How well does the product hold up? How reliable is it over time? How responsive is customer support when problems arise? These questions, critical to purchasing decisions, are unanswerable in traditional review timeframes.

The most valuable product information often emerges only with extended use. The laptop that seemed excellent becomes frustrating as the battery degrades. The appliance that tested well develops reliability issues after the warranty expires. The software that impressed at launch becomes bloated with unwanted features. Reviews capture the honeymoon period; ownership includes the entire relationship.

The Manipulation Problem

User review platforms face systematic manipulation that makes aggregate ratings unreliable indicators of product quality.

flowchart TB

subgraph "Manipulation Tactics"

A[Incentivized Reviews] --> E[Inflated Ratings]

B[Fake Reviews] --> E

C[Competitor Sabotage] --> F[Deflated Ratings]

D[Review Removal Requests] --> G[Survivorship Bias]

end

subgraph "Platform Responses"

H[Detection Algorithms] --> I[Arms Race]

J[Verification Systems] --> K[Partial Mitigation]

L[Legal Action] --> M[Limited Deterrence]

end

E --> N[Unreliable Ratings]

F --> N

G --> N

I --> O[Sophisticated Manipulation]

O --> AFake reviews are the most obvious manipulation. Sellers purchase positive reviews for their products and negative reviews for competitors. The review farms that provide this service have become sophisticated—using varied language, diverse reviewer profiles, and natural-seeming posting patterns to evade detection.

Platforms invest heavily in detecting fake reviews, but the arms race continues. Detection algorithms identify patterns; manipulators evolve to avoid those patterns. Machine learning catches some fake reviews; other fake reviews are written by humans specifically to evade machine learning. The cat-and-mouse game produces an unknowable baseline of fake content in any platform’s review corpus.

Incentivized reviews present subtler manipulation. The seller offers discount codes, free products, or other incentives in exchange for reviews. These aren’t fake—the reviewer actually uses the product—but the incentive structure creates bias. People who received something free rate it more positively than people who paid full price. The “verified purchase” badge doesn’t distinguish between incentivized and non-incentivized purchases.

The manipulation isn’t always from sellers. Competitors post negative reviews to damage rivals. Disgruntled individuals post revenge reviews unrelated to product quality. Ideological actors organize review campaigns for or against products based on company politics rather than product merit.

The aggregation that should make user reviews valuable—averaging thousands of opinions should converge on truth—fails when the sample is systematically corrupted. An average of manipulated ratings produces a manipulated average. The 4.2-star product might genuinely be worse than the 3.8-star product if the former has more fake positives and the latter has more fake negatives.

Smart consumers know this and adjust accordingly. But the adjustment requires guessing the manipulation level, which varies unpredictably across products, categories, and platforms. The mental overhead of calibrating for manipulation defeats the purpose of using reviews to simplify decisions.

The Selection Bias Problem

Who writes reviews? Not a representative sample of purchasers. This selection bias systematically distorts the information available to prospective buyers.

Reviews skew toward extremes. Delighted customers write reviews to express enthusiasm. Frustrated customers write reviews to express anger. Satisfied-but-unremarkable experiences generate no reviews because there’s nothing notable to say. The distribution of reviews is bimodal—lots of fives, lots of ones, fewer in between—while the distribution of actual experiences is probably normal.

This bimodal selection creates misleading impressions. The product with mostly five-star and one-star reviews might actually be fine for most people—the satisfied majority simply didn’t bother writing. The product with consistently three-star reviews might actually be more reliable—the moderate satisfaction motivated more representative sampling.

Selection bias also affects who reviews within each extreme. The one-star reviewer who writes a detailed complaint might have unusual expectations or unusual bad luck. The five-star reviewer writing enthusiastic praise might be easily impressed or reviewing during the honeymoon period. Neither represents the typical experience.

Certain personality types are more likely to write reviews. People with time to write reviews differ from people without time. People motivated to share opinions differ from people who keep opinions private. People comfortable with public expression differ from people who avoid it. The reviewing population isn’t the purchasing population.

This matters because product fit depends on personal characteristics. A product perfect for the review-writing personality type might disappoint the non-review-writing personality type. The consensus visible in reviews reflects the consensus of reviewers, which may not match the consensus of all users.

Mochi doesn’t write reviews, but if she did, she’d represent a biased sample: cats who are literate, have opposable thumbs for typing, and care enough about water fountains to document their opinions. The silent majority of cats would go unrepresented. Consumer reviews face an analogous problem.

How We Evaluated

The analysis in this article emerges from systematic examination of the review ecosystem:

Step 1: Review Corpus Analysis

I examined hundreds of reviews across multiple product categories, tracking patterns in structure, language, recommendation logic, and commercial relationships. The affiliate saturation and format convergence were unmistakable.

Step 2: Platform Data Examination

Analysis of user review platforms included studying rating distributions, reviewer profiles, and temporal patterns. Academic research on review manipulation provided context for the observed patterns.

Step 3: Personal Purchase Tracking

Over several years, I tracked my own purchases where reviews influenced decisions, comparing predicted outcomes (based on reviews) to actual outcomes (based on ownership). The correlation was weaker than expected.

Step 4: Expert Interviews

Conversations with professional reviewers, platform employees, and researchers studying online commerce revealed insider perspectives on the incentive structures and manipulation dynamics.

Step 5: Literature Review

Academic research on consumer decision-making, review psychology, and platform economics provided theoretical frameworks for understanding observed phenomena.

Step 6: Alternative Source Testing

I experimented with non-review information sources—forums, direct user communities, professional consultations—comparing their utility to traditional reviews.

The Expertise Deficit Problem

Many product categories require expertise to evaluate meaningfully. Most reviewers lack this expertise. The result is reviews that confidently assess things the reviewer isn’t qualified to assess.

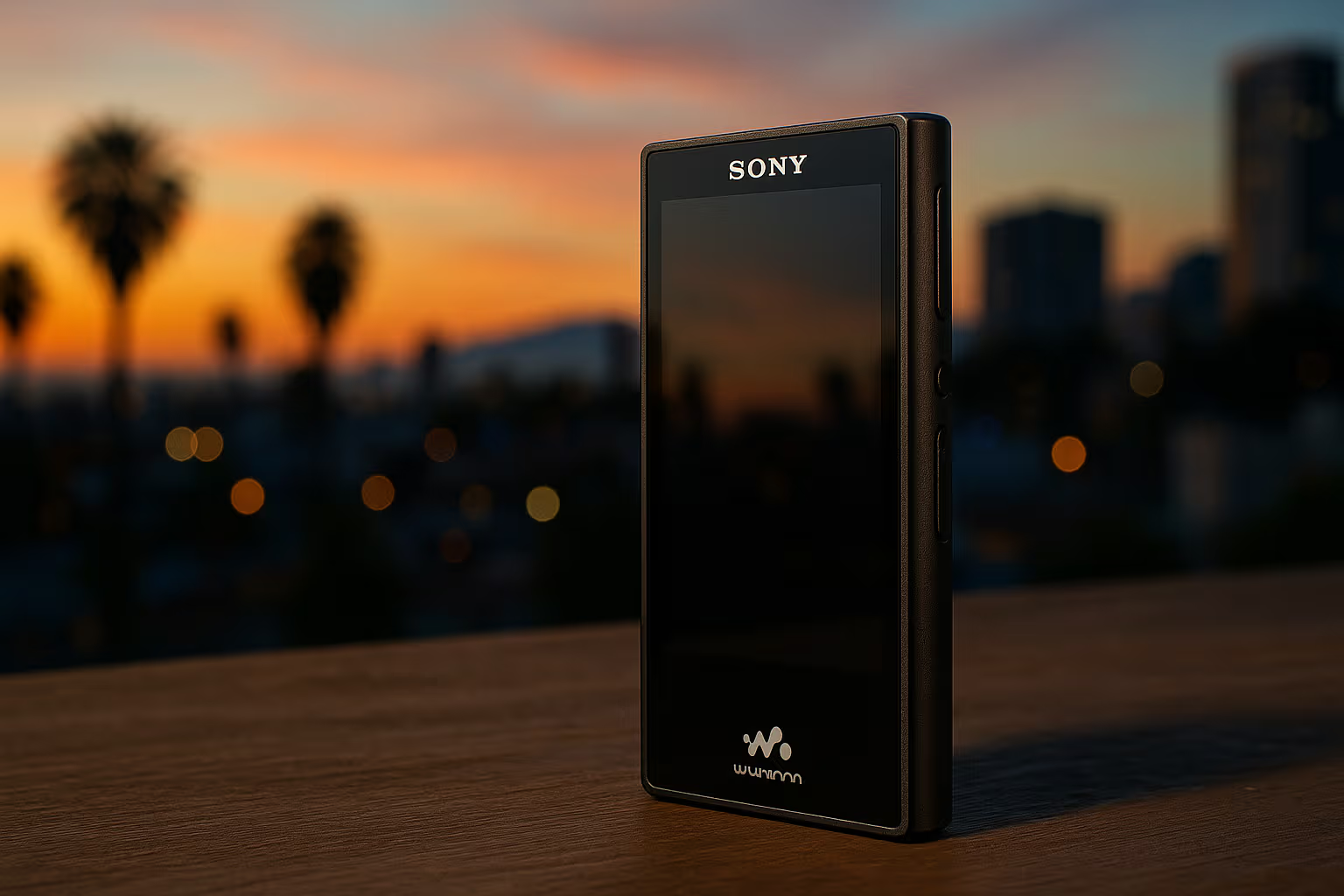

Consider audio equipment reviews. Evaluating headphones requires understanding of frequency response, driver technology, amplification requirements, and psychoacoustics. Most headphone reviewers lack this background. They offer subjective impressions—“sounds good to me”—that tell other listeners little because audio perception is personal and the listener’s context differs from the reviewer’s.

The same expertise deficit appears across categories. Camera reviews by non-photographers. Software reviews by non-developers. Kitchen equipment reviews by non-cooks. The reviewer’s confidence exceeds their competence, and the reader can’t easily distinguish expert assessment from amateur impression.

Professional reviewers sometimes have relevant expertise, but not always. The tech journalist reviewing laptops may understand specifications without understanding the actual work those laptops will be used for. The automotive journalist reviewing cars may understand performance metrics without understanding daily commuting needs. Expertise in evaluation differs from expertise in use.

The expertise problem extends to testing methodology. Proper product evaluation requires controlled conditions, relevant benchmarks, and statistical rigor. Most reviews use none of these. The reviewer’s personal experience, however genuine, represents a single data point with uncontrolled variables. Drawing general conclusions from this is methodologically unsound, yet every review does exactly that.

Some publications employ specialized experts and rigorous testing protocols. Consumer Reports has decades of methodology development. Wirecutter employs subject-matter experts for each category. These sources provide genuinely useful information. But they’re islands in an ocean of amateur content, and finding them requires knowing to look for them.

The Recommendation Matching Problem

Reviews typically end with recommendations: buy this, skip that, consider this alternative. These recommendations assume the reviewer knows what you need. They rarely do.

The “best” laptop depends entirely on what you need a laptop for. The “best” camera depends on what you’ll photograph. The “best” anything depends on your specific requirements, constraints, and preferences. Universal recommendations pretend these differences don’t exist.

“Best value” recommendations are particularly problematic. Value means different things to different buyers. Someone prioritizing initial cost defines value differently than someone prioritizing total cost of ownership. Someone with abundant time but limited money defines value differently than someone with limited time but abundant money. “Best value” universalized is meaningless.

The listicle format compounds this problem. “10 Best Wireless Earbuds” must recommend ten products, regardless of whether ten distinct recommendation scenarios exist. The list includes products nobody should buy just to fill slots. The reader can’t distinguish genuine recommendations from list-padding.

Better reviews would segment recommendations by context: “best for commuting,” “best for gym use,” “best for audio production.” Some reviews do this. Most don’t, because segmented recommendations require more expertise and produce more complex content that performs worse in search rankings and engagement metrics.

The structural incentives favor universal recommendations even though contextual recommendations would serve readers better. Simple advice generates more clicks than complex advice. “Buy this one” outperforms “here’s how to figure out what you need” in engagement metrics. The review ecosystem optimizes for engagement, producing recommendations optimized for engagement rather than accuracy.

Generative Engine Optimization

The concept of Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) provides a useful framework for understanding why reviews fail and what might work better.

In GEO terms, traditional reviews are low-value content that generates minimal insight per unit of consumption. Reading ten reviews doesn’t produce ten times the insight of reading one review—the redundancy is enormous, the incremental information minimal.

graph TB

subgraph "Traditional Review Value"

A[Review 1] --> B[Information Gained]

C[Review 2] --> D[Marginal Gain]

E[Review 3] --> F[Minimal Gain]

G[Review 10] --> H[Near Zero Gain]

end

subgraph "Optimal Information Sources"

I[Expert Community] --> J[Contextual Answers]

K[Long-term User] --> L[Durability Insights]

M[Comparative Testing] --> N[Controlled Data]

O[Personal Trial] --> P[Perfect Context Match]

end

B --> Q[Purchase Decision]

D --> Q

F --> Q

H --> Q

J --> Q

L --> Q

N --> Q

P --> Q

style I fill:#90EE90

style K fill:#90EE90

style M fill:#90EE90

style O fill:#90EE90GEO thinking suggests seeking information sources with higher value density. Instead of reading ten redundant reviews, find one expert who matches your context. Instead of aggregating biased ratings, find a community of actual users discussing their experiences. Instead of trusting recommendations, test the product yourself if possible.

The highest-value information often comes from sources that aren’t formatted as reviews at all. Forum discussions where users solve problems reveal real-world experiences. Reddit threads where enthusiasts debate alternatives reveal nuanced trade-offs. YouTube videos showing actual use reveal what static reviews can’t capture. These sources lack the polish of professional reviews but often contain more useful information.

GEO also suggests that generating your own decision criteria before consuming reviews produces better outcomes than letting reviews define criteria. Know what matters to you before reading what mattered to reviewers. This prevents the common trap of optimizing for the reviewer’s priorities rather than your own.

Applying GEO to product research means optimizing for decision quality rather than information quantity. Fewer, better sources outperform more, worse sources. Time spent clarifying your own needs outperforms time spent reading about others’ needs. The review ecosystem encourages information accumulation; GEO thinking encourages information curation.

What Actually Works

Despite the problems enumerated above, good purchasing information exists. Finding it requires knowing where to look and how to evaluate what you find.

Specialized Communities

Forums and communities dedicated to specific product categories contain accumulated wisdom from experienced users. The camera forum has photographers who’ve used equipment for years. The audio forum has listeners who’ve compared dozens of headphones. The cooking forum has cooks who’ve tested appliances through actual cooking.

These communities have their own biases—enthusiasts sometimes overvalue niche features—but they provide contextual depth that generic reviews lack. More importantly, you can ask questions and receive responses tailored to your specific situation. The interactivity transforms one-way information consumption into dialogue.

Long-Term Ownership Reports

Some sources specialize in long-term evaluation: how products hold up over years rather than days. These reports reveal durability, reliability, and sustained satisfaction that initial reviews can’t assess. Seeking these sources—often buried below the fresher reviews in search results—provides information unavailable elsewhere.

Return Policy Exploitation

The highest-quality information source is personal experience. For products with generous return policies, buying, testing, and potentially returning provides perfect context match and eliminates all the problems of mediated information. This isn’t always practical, but when it is, it’s superior to any review.

Expert Consultation

For high-stakes purchases, consulting actual experts may be worth the cost. A photographer advising on cameras. A developer advising on laptops. A chef advising on kitchen equipment. These consultations provide contextually appropriate recommendations that generic reviews can’t match.

Manufacturer Comparisons

Counterintuitively, manufacturer specifications and feature lists sometimes provide more useful information than reviews. They state facts rather than opinions. They’re comparable across products. They don’t pretend to know what you need. Combined with clear understanding of your own requirements, specifications enable informed comparison without the noise of subjective assessment.

The Self-Review Paradox

This article reviews product reviews—making it part of the phenomenon it critiques. The paradox is unavoidable. Any critique of information quality is itself information subject to the same quality concerns.

The affiliate bias that corrupts product reviews doesn’t apply here—there’s no commission for convincing you that reviews are problematic. But other biases remain. I have a perspective; perspectives create blindspots. I have experiences; experiences may not generalize. The critique is genuine, but critiquing is not the same as solving.

What I can offer is transparency about the analysis and humility about its limits. The problems described are real and well-documented. The solutions suggested may work for some readers and not others. The goal isn’t to provide definitive answers but to provide frameworks for thinking more clearly about a genuinely difficult problem.

Mochi, for her part, resolved the cat water fountain question through direct action. She rejected three fountains I purchased based on reviews, eventually settling on a ceramic model that no review recommended. Her selection criteria—undocumented, unknowable, but apparently consistent—produced better results than my hours of research. Sometimes the best review process is no review process.

The Future of Reviews

The problems with reviews are structural, but structures can change. Several developments might improve the review ecosystem over time.

AI-Powered Personalization

Generative AI could transform review consumption by synthesizing available information for your specific context. Instead of reading generic reviews, you’d describe your needs and receive customized assessments based on aggregated data. The AI would filter for relevant contexts, adjust for known biases, and present what actually matters for your situation.

This future isn’t here yet—current AI struggles with the accuracy and nuance required—but the trajectory points toward it. The review as a standalone article may become obsolete, replaced by dynamic information synthesis tailored to each reader.

Verified Usage Data

Platforms could require verified long-term ownership for reviews, filtering out immediate impressions and incentivized responses. Smart products could automatically contribute usage data—how often the product is actually used, whether it’s returned, how long it lasts. This data, aggregated and anonymized, would reveal patterns that subjective reviews can’t capture.

Reputation Systems

Reviewer reputation systems could weight reviews by demonstrated expertise and historical accuracy. The reviewer whose recommendations consistently matched buyer outcomes would carry more weight than the reviewer whose recommendations consistently disappointed. Building such systems is technically challenging but not impossible.

Economic Realignment

The affiliate model could yield to alternatives that better align incentives. Subscription-supported review publications have no per-recommendation incentive to corrupt. Consumer-funded testing organizations answer to buyers rather than sellers. Economic experimentation might produce models that support honest assessment.

None of these developments are guaranteed. The current equilibrium—lots of low-quality reviews generating enough value to sustain themselves—might persist indefinitely. But the consumer frustration with the status quo creates pressure for change, and pressure eventually produces adaptation.

Practical Decision Framework

For readers making purchasing decisions now, rather than waiting for systemic improvement, here’s a practical framework:

Step 1: Define Your Requirements First

Before reading any reviews, write down what you actually need. Be specific. This prevents reviews from redefining your priorities toward what they happen to evaluate well.

Step 2: Identify Your Context

What’s unusual about your situation? Your use case, environment, technical sophistication, budget constraints? These contextual factors determine which reviews might be relevant and which are noise.

Step 3: Seek Context-Matched Sources

Find reviewers or communities that share your context. The photographer reviewing cameras for photographers. The developer reviewing laptops for developers. The match matters more than the review’s polish or prominence.

Step 4: Weight Long-Term Over Short-Term

Actively seek long-term ownership reports and deprioritize initial impressions. The information is harder to find but more valuable for predicting your own experience.

Step 5: Triangulate Across Sources

Don’t trust any single source. Look for patterns across independent sources. Agreement among unrelated reviewers is more informative than any individual review.

Step 6: Test When Possible

If return policies allow, treat purchases as experiments. Your own experience in your own context is the gold standard. Reviews are approximations; direct experience is data.

Step 7: Accept Uncertainty

Perfect information doesn’t exist. Some purchases will disappoint despite good research. Budget for this uncertainty—financially and emotionally. The goal is better decisions, not perfect decisions.

The Information Diet Perspective

The review problem is a specific case of a broader information problem: more content doesn’t mean more understanding. The same dynamics that make most reviews unhelpful make most content unhelpful.

Developing a healthy information diet means being selective about consumption, skeptical about sources, and efficient about extraction. It means recognizing that your time is finite and most content isn’t worth that time. It means developing the critical skills to identify the signal amid the noise.

These skills transfer beyond product reviews. The same selection bias, manipulation, and context mismatch appear in news, analysis, and opinion across domains. Learning to navigate the review ecosystem builds capabilities applicable everywhere information competes for attention.

Mochi’s information diet is exemplary. She ignores almost everything, focusing exclusively on signals that matter: food-related sounds, comfortable resting spots, potential prey (real or imaginary). Her filtering is aggressive, perhaps too aggressive, but she never suffers from information overload. Humans can’t be quite so selective, but the principle—ignore most things, focus on what matters—applies.

The review ecosystem will continue producing content. That content will continue being mostly unhelpful. The solution isn’t changing the ecosystem—individuals can’t do that—but changing how you interact with it. Consume less. Curate more. Trust judgment over volume. Make decisions confidently despite incomplete information, because complete information was never available anyway.

Final Thoughts

Most product reviews have zero value for real decision-making because they’re optimized for purposes other than helping you decide. They’re optimized for affiliate revenue, engagement metrics, search rankings, and content volume. Your informed decision is at best a side effect and at worst an impediment to their actual goals.

This isn’t a moral failing of individual reviewers—most genuinely want to help. It’s a structural outcome of incentive systems that reward quantity over quality, engagement over accuracy, and universal appeal over contextual relevance. The system produces what the system rewards.

The consumer’s response must be systematic too. Understanding the structural problems enables navigating around them. Knowing why reviews fail helps identify the exceptions that don’t. Developing alternative information strategies reduces dependence on fundamentally compromised sources.

The work is harder than it should be. Finding useful product information requires more effort than the information ecosystem implies. The easy path—reading top search results, trusting aggregated ratings, following confident recommendations—leads to mediocre decisions. Better decisions require deliberate effort to circumvent the default.

This effort is worth it for significant purchases. The laptop you’ll use for years, the appliance that will occupy kitchen space, the tool that will shape your workflow—these decisions merit the investment of finding actually useful information. For minor purchases, the review ecosystem’s failures matter less; disappointing outcomes are easier to absorb.

The ultimate skill is knowing when to research and when to just decide. Paralysis in pursuit of perfect information is its own failure mode. Sometimes the best decision is a quick decision based on minimal research, accepting the uncertainty and moving on. Reviews won’t save you; your own judgment, informed but not paralyzed by information, is what actually produces good outcomes.

Mochi is sleeping now, curled next to the water fountain she chose through inscrutable means. She’s hydrated and content. The reviews I read contributed nothing to this outcome. Perhaps that’s the most honest assessment of product reviews I can offer: even when you read them carefully, the outcome often depends on factors they never mentioned.

Choose wisely. Trust yourself. And maybe just buy the thing and see if it works.