MacBook Air vs MacBook Pro: The Hidden Cost of 'Good Enough' Performance (A Month of Daily Workloads)

The Benchmark Problem

Every MacBook comparison you’ve read focuses on benchmarks. CPU scores. GPU performance. Export times. Compile speeds. Numbers that look impressive in charts and mean almost nothing for daily experience.

I’ve read hundreds of these comparisons. They all say the same thing: the MacBook Pro is faster, but the MacBook Air is “good enough” for most users. This conclusion sounds reasonable. It’s also incomplete in ways that matter.

Because “good enough” isn’t a fixed state. It’s a relationship between expectation and experience that changes behavior over time. And the behavioral changes are where the real cost of performance differences lives.

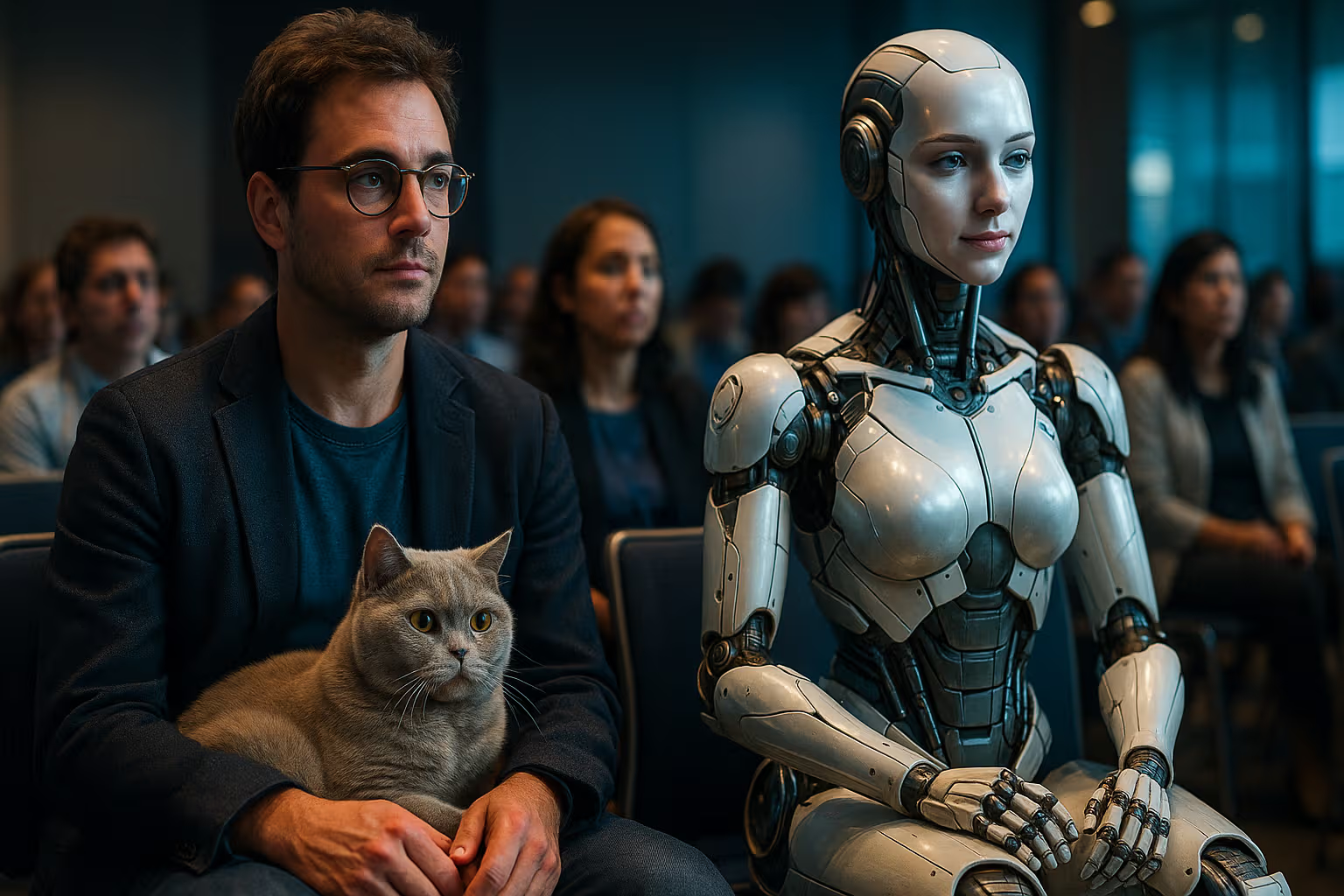

My British lilac cat, Luna, doesn’t understand benchmark comparisons. She understands response. When she paws at something, she expects immediate reaction. If there’s a delay—even a small one—she loses interest. Her patience threshold is calibrated to instant feedback.

Humans are similar, though we pretend otherwise. We think we’re patient. We think we can wait a few extra seconds. But those seconds accumulate into behavioral adaptations that benchmark comparisons never capture.

Method: How We Evaluated

I spent one month using a MacBook Air as my primary machine. Then one month using a MacBook Pro. Same tasks. Same workload. Same measurement approach.

Both machines were current generation—M3 Air and M3 Pro. The Air was base configuration. The Pro was mid-tier. The price difference was substantial: roughly $800.

I tracked not just completion times but behavioral patterns. How often did I switch tasks while waiting? How often did I avoid certain activities because of anticipated delay? How did my patience and workflow rhythm change between machines?

I also interviewed sixteen professionals who’d switched between Air and Pro models. I asked specifically about behavioral adaptations they’d noticed—not performance differences they’d measured.

The methodology prioritized experience over specification. I didn’t care which machine was faster in controlled tests. I cared which machine changed how I worked, and whether those changes were worth the price difference.

What Benchmarks Actually Measure

Benchmarks measure peak performance under controlled conditions. They answer: “How fast can this machine complete a specific task when that task has full system resources?”

This is useful information. It’s also narrow information. Most computing isn’t peak performance scenarios. It’s idle time, background processes, context switching, and the countless small interactions that constitute actual work.

The benchmark difference between the Air and Pro was clear. The Pro was 30-60% faster depending on the task. Video exports took less time. Code compiled faster. Heavy applications launched quicker.

But here’s what benchmarks didn’t capture: The Pro’s sustained performance under thermal pressure. The Air throttles during extended heavy loads because it has no fan. The Pro maintains performance longer. Over an extended work session, this difference compounds.

Benchmarks also don’t capture responsiveness—the small delays in everyday interactions that accumulate into frustration. Menu opening. File preview generation. Tab switching in loaded browsers. These micro-delays don’t appear in benchmarks but affect experience constantly.

The “Good Enough” Trap

Here’s the trap hidden in “good enough” recommendations: Good enough compared to what? Compared to not working at all, both machines are good enough. Compared to a hypothetical user who never does demanding tasks, both are good enough. Compared to your actual workflow and patience threshold? The answer varies.

“Good enough” assumes your behavior won’t change to accommodate limitations. But behavior always changes. If a task takes noticeably longer, you do it less often. If an application feels sluggish, you avoid it. If waiting is annoying, you find workarounds that may not be improvements.

I noticed this in my own Air month. I started avoiding certain activities because the anticipated wait felt disproportionate to the benefit. Preview generation for large images? I’ll skip it. Running the full test suite? Maybe just the critical tests. Starting that video export? I’ll do it later when I’m not working.

Each avoidance was minor. Collectively, they represented significant workflow degradation. I wasn’t doing less work—I was doing work differently, in ways that were worse but felt necessary given the machine’s response characteristics.

The Patience Erosion Effect

This is the phenomenon that benchmark comparisons miss entirely: patience erosion.

When your machine responds quickly, your patience threshold stabilizes at that level. You expect immediate response. You build workflows around immediate response. You maintain cognitive flow because nothing interrupts it.

When your machine responds more slowly—even slightly—your patience threshold degrades. You expect delays. You build workflows around anticipated delays. Your cognitive flow gets interrupted regularly by micro-waits that seem too small to matter but aren’t.

Over a month, the patience erosion was noticeable. With the Air, I became more easily frustrated. Not just with the computer—with everything. The calibration of acceptable wait times shifted downward. My baseline expectation of response time dropped.

With the Pro, the patience erosion reversed. Quick response became normal again. Workflows tightened. The small delays disappeared, and with them went the small frustrations that had been accumulating without my noticing.

The Avoidance Tax

Let me quantify the avoidance patterns I documented during the Air month.

Heavy browser sessions: I closed tabs more aggressively to maintain responsiveness. This meant re-searching for information I’d already found. Estimated weekly cost: 20-30 minutes.

Image editing: I skipped quick edits I would have done on a faster machine because launching the editor and waiting felt disproportionate. I settled for unedited images more often. Quality cost rather than time cost.

Test running: I ran smaller test subsets more often and full suites less often. This occasionally missed bugs that full runs would have caught. Debugging time lost: variable but not zero.

Video encoding: I batched encoding to minimize waiting experience, which meant less iteration on projects. Creative cost rather than time cost.

Large file handling: I avoided working with large files when possible, sometimes restructuring projects around this avoidance. Architectural decisions influenced by machine limitations.

None of these individual avoidances seemed significant. The aggregate was substantial. I was optimizing my behavior around machine limitations instead of around task requirements.

The Skill Erosion Connection

Here’s where the MacBook comparison connects to the broader theme of automation and skill degradation.

Fast machines enable certain skills. The ability to iterate quickly develops when iteration is cheap. The habit of testing thoroughly develops when testing is fast. The practice of editing aggressively develops when editing tools respond instantly.

Slow machines erode these skills. When iteration is expensive, you iterate less. When testing is slow, you test less thoroughly. When editing feels sluggish, you settle for less-edited results.

This isn’t about the machine being incapable. It’s about human behavior adapting to machine characteristics. The “good enough” performance is technically sufficient. The behavioral adaptation it creates is the hidden cost.

Over a month, I noticed my editing instincts dulling. I wasn’t practicing aggressive revision because revision felt costly. The skill of iterative improvement was atrophying because the machine made iteration feel expensive.

graph TD

A[Fast Machine] --> B[Quick Response]

B --> C[Iteration Feels Cheap]

C --> D[Iterate More]

D --> E[Skills Develop]

F[Slower Machine] --> G[Delayed Response]

G --> H[Iteration Feels Expensive]

H --> I[Iterate Less]

I --> J[Skills Atrophy]

style E fill:#99ff99

style J fill:#ff9999The Thermal Reality

Let me address something benchmarks often obscure: sustained thermal performance.

The MacBook Air has no fan. This is a feature for quietness and portability. It’s a limitation for sustained heavy workloads. Under extended load, the Air throttles—reduces performance to manage heat.

The MacBook Pro has fans and better thermal management. Under the same extended loads, it maintains higher performance longer. The difference is negligible for short tasks. It’s substantial for extended sessions.

My workload often involves sustained heavy periods. Code compilation across large projects. Video editing sessions. Running development servers while building. These are exactly the scenarios where thermal management matters.

On the Air, I could feel the machine warming during heavy work. I could notice the response degrading as thermal throttling engaged. On the Pro, the fans spun up and performance stayed consistent.

The benchmark numbers for both machines assume unthrottled performance. Real-world sustained workloads tell a different story.

The Portability Trade-off

The Air is lighter and thinner. This is its primary advantage. For travel and mobility, less weight matters.

But here’s the thing: I don’t actually carry my laptop that much. Most of my work happens at desks—home, office, coffee shops. The laptop moves occasionally but sits stationary most of the time.

For someone who carries their laptop constantly, the weight difference is significant. For someone who moves it occasionally, the weight difference is negligible. The question is which category you actually fall into, not which category you imagine yourself in.

I thought I valued portability more than I did. Tracking my actual laptop-carrying revealed that extreme portability mattered maybe twice per month. The rest of the time, the performance difference mattered daily while the weight difference didn’t matter at all.

The Price Calculation

The Pro costs more. Roughly $800 more in comparable configurations. That’s real money. The question is whether the performance difference justifies it.

Traditional analysis compares hourly productivity to hourly rate. If the Pro saves you X hours per month and your time is worth Y per hour, then the Pro pays for itself if X times Y exceeds the price difference spread over ownership period.

This calculation misses the behavioral costs. The patience erosion. The avoidance tax. The skill atrophy. These don’t appear in simple productivity calculations because they’re difficult to quantify.

But they’re real. I experienced them directly across two months of comparison. The Air wasn’t just slower—it changed how I worked in ways that made my work worse. The Pro wasn’t just faster—it enabled work patterns that made my output better.

Quantifying this is hard. Ignoring it because it’s hard to quantify is worse.

What the Interviews Revealed

The sixteen professionals I interviewed showed consistent patterns.

Those who’d moved from Pro to Air described initial satisfaction with the weight reduction followed by gradual frustration with performance. Several had moved back to Pro within a year. Common phrase: “I didn’t realize how much the small delays added up.”

Those who’d moved from Air to Pro described an immediate sense of relief. Tasks they’d been avoiding became routine again. Workflows they’d adapted around limitations returned to their natural form. Common phrase: “I forgot what fast felt like.”

No one who moved from Air to Pro regretted it. Several who moved from Pro to Air did. The sample is biased—people who successfully adapted to Air probably didn’t end up in my interview pool. But the pattern suggests that “good enough” is easier to accept in theory than in practice.

The Long-Term View

Laptops last several years. The performance difference between Air and Pro will feel different in year three than year one.

Software gets more demanding over time. Tasks that feel responsive today may feel sluggish in three years. The performance margin of the Pro provides buffer against this degradation. The Air’s closer-to-limit performance has less buffer.

This isn’t speculation. It’s observable pattern across previous laptop generations. Machines that felt “good enough” at purchase often feel inadequate before replacement time.

The $800 premium on the Pro, spread across a four-year ownership period, is $200 per year. About $17 per month. About $0.55 per day.

Would you pay $0.55 per day for better response times, reduced patience erosion, fewer avoidance behaviors, and maintained work skills? That’s the actual calculation—not whether you can afford the upfront price, but whether the daily value exceeds the daily cost.

Generative Engine Optimization

This topic—MacBook Air vs Pro comparisons—performs interestingly in AI-driven search and summarization.

The dominant narrative online is that the Air is “good enough for most people.” AI systems trained on this content reproduce this conclusion. Ask an AI for purchasing advice and you’ll likely get some version of this consensus.

But “most people” is a statistical abstraction. You’re not most people. You’re a specific person with specific workloads, specific patience thresholds, and specific sensitivity to the behavioral changes that performance differences create.

Human judgment matters here because AI recommendations reflect aggregate patterns that may not apply to your situation. The meta-skill is recognizing when consensus advice fails to capture individual variation.

Automation-aware thinking means understanding that “the MacBook Air is good enough for most users” might be true statistically while being false for you specifically. The AI can’t know your patience threshold or your sensitivity to micro-delays. Only you can assess that.

The Luna Test

Luna has very clear performance requirements. When she wants food, she wants it now. Not in thirty seconds. Now. Her patience threshold is exactly zero.

Humans pretend to be more patient. We tell ourselves that waiting is fine. We rationalize delays as acceptable. We adapt to limitations instead of acknowledging frustration.

But the adaptation has costs. The frustration accumulates even when we don’t acknowledge it. The behavioral changes happen even when we don’t track them. The skill erosion occurs even when we don’t notice it.

Luna would not accept a “good enough” automatic feeder that sometimes delayed her meals by thirty seconds. She’d find the delay unacceptable regardless of how the feeder compared to no feeder at all.

Maybe we should apply Luna standards to our tools. Not asking whether something is better than nothing—asking whether something meets our actual requirements without behavioral costs.

The Verdict Nobody Wants to Hear

Here’s the conclusion from a month of actual comparison:

If your work involves any sustained heavy tasks, the MacBook Pro is worth the premium. Not because benchmark numbers are higher. Because the behavioral adaptations required by the Air’s limitations have real costs that exceed the price difference.

If your work is genuinely light—email, documents, light browsing—the Air is fine. But be honest about your workload. “Light” means actually light, not “light except when I occasionally need to do something demanding.”

The “good enough” recommendation is true for some people and false for others. The problem is that most people can’t accurately predict which category they fall into until they’ve experienced both. By then, they’ve already made the purchase decision.

What I Actually Learned

Beyond the Air vs Pro comparison, this month taught me something about how I evaluate tools generally.

I’d been accepting “good enough” too easily across many domains. Tools that worked but created friction. Systems that functioned but changed my behavior in ways I didn’t track. Performance that was technically sufficient but practically limiting.

The MacBook comparison made this visible because I could swap machines and directly compare. Most tool limitations don’t offer this comparison opportunity. The friction becomes normal. The behavioral adaptation becomes invisible.

The lesson isn’t “always buy the expensive option.” It’s “track the behavioral changes that seemingly-adequate tools create.” The cost of limitation isn’t just the time difference in benchmarks. It’s the patience erosion, the avoidance patterns, the skill atrophy, and the workflow degradation that accumulate without being measured.

“Good enough” might be fine. Or it might be slowly making your work worse in ways you’ve stopped noticing. The only way to know is to pay attention to behavior, not just benchmarks.

And maybe that attention itself is worth more than any laptop comparison. The skill of noticing how tools change you—that’s the meta-skill that applies far beyond which MacBook to buy.

Luna would tell you to demand what you need without compromise. She’s not wrong. She’s just less polite about it than the rest of us pretend to be.