How AI Is Changing Creative Work: Tool or Competition?

The question arrives in my inbox at least once a week now, phrased slightly differently each time but always pointing at the same anxiety: “Is AI going to replace me?” The asker is sometimes a writer, sometimes a designer, sometimes a developer who spends half their time on creative problems. They’ve seen the demos. They’ve played with the tools. And they’re scared.

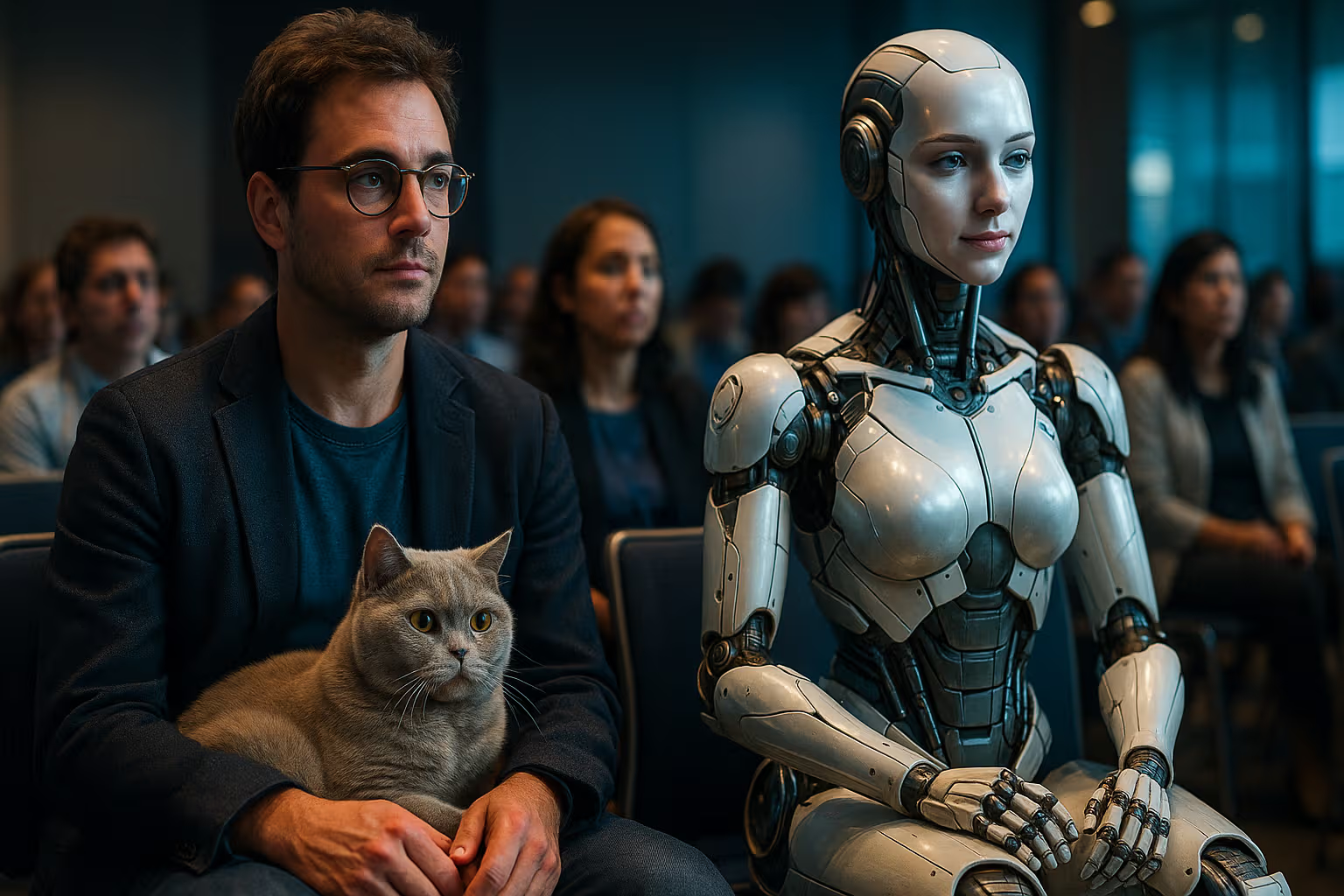

My British lilac cat, Mochi, has no such concerns. She watches me work with AI tools daily—sees me prompt, iterate, refine, reject, and occasionally marvel at what emerges. From her perspective, I’m still the one who types, who decides, who controls the treats. The machine is furniture. Important furniture, perhaps, like the refrigerator, but furniture nonetheless.

There’s wisdom in that feline perspective, but it’s also incomplete. The refrigerator doesn’t get better at anticipating what food I want. AI does. The refrigerator doesn’t learn from every meal I prepare. AI does. The question isn’t whether AI will replace creative workers—it’s how the relationship between human creativity and machine capability will evolve, and what skills will matter in that evolution.

I’ve spent the last three years working intensively with AI tools across multiple creative domains: writing, coding, design, and music. Not as experiments or demos, but as part of real production work with real deadlines and real quality standards. What I’ve learned doesn’t fit neatly into the “AI is just a tool” or “AI is taking over” narratives. The reality is messier, more interesting, and more nuanced.

This article is my attempt to share that reality. Not predictions about what might happen in ten years—those are usually wrong. But observations about what’s happening now, patterns I’ve noticed, and frameworks for thinking about this that might help you navigate your own creative relationship with AI.

The False Binary

The “tool or competition” framing is seductive but misleading. It assumes these are the only two options, and it assumes they’re mutually exclusive. Neither is true.

Consider the history of creative technology. When Photoshop emerged, it was simultaneously a tool that empowered designers and a force that eliminated certain jobs (photo retouchers, for instance, who spent their careers doing work that Photoshop automated). It was both tool and competition, depending on who you were and what you did.

AI follows this pattern but with a crucial difference: scope. Photoshop affected a specific domain of creative work. AI affects nearly all of them. Writing, visual art, music, code, video—there’s almost no creative medium untouched. This breadth changes the calculus. You can’t simply move to an unaffected field because there are few unaffected fields.

But here’s where the “competition” framing breaks down: AI doesn’t compete the way humans do. It doesn’t want your job. It doesn’t want anything. It’s a capability that exists and that various actors—including you—can harness. The competition isn’t you versus AI. It’s you versus other humans who may be using AI more effectively than you.

This reframing matters. If AI is your competitor, the rational response is resistance or despair. If AI is a capability that anyone can use, the rational response is to learn to use it well. One framing leads to paralysis. The other leads to adaptation.

Mochi just demonstrated adaptation by figuring out how to open the cabinet where her treats are stored—a problem I thought I’d solved with a child lock. She didn’t view the lock as competition. She viewed it as a puzzle to solve with her existing capabilities. The cabinet is now treat-accessible. I need a better lock.

How We Evaluated: A Step-by-Step Method

To understand how AI actually affects creative work, I spent eighteen months tracking my own creative output across projects that used AI assistance and projects that didn’t. Here’s the methodology:

Step 1: Categorize the Work

I divided my creative work into categories:

- Writing (articles, documentation, marketing copy)

- Code (features, debugging, architecture)

- Design (UI mockups, graphics, presentations)

- Strategy (planning, analysis, decision-making)

For each category, I tracked projects separately based on AI involvement.

Step 2: Measure Time and Quality

For each project, I recorded:

- Total time invested

- Time in different phases (research, drafting, refinement, review)

- Quality assessment (my own rating plus external feedback where available)

- Revision rounds required

- Final satisfaction score

Step 3: Analyze the Patterns

After eighteen months, I had enough data to see patterns. Some were expected. Others surprised me.

Step 4: Validate with Other Creatives

I shared findings with a dozen other creative professionals working across different domains. Their experiences either confirmed or complicated my observations.

Step 5: Synthesize Principles

From the data and discussions, I extracted principles about when AI helps, when it doesn’t, and what determines the difference.

The rest of this article shares those principles. They’re not universal truths—creative work is too varied for that. But they’re patterns robust enough to be useful.

Where AI Actually Helps

Let’s start with the positive. AI genuinely improves certain aspects of creative work.

First Drafts and Ideation

The blank page is creativity’s oldest enemy. AI demolishes it. Whether you’re writing an article, designing a layout, or starting a new codebase, AI can generate initial material that gives you something to react to.

This matters more than it might seem. Human creativity often works better in edit mode than in generate mode. We’re excellent at recognizing quality—“yes, that’s right” or “no, that’s wrong”—but less excellent at generating quality from nothing. AI inverts the problem. Instead of generating from scratch, you’re curating and refining from abundance.

My writing process has fundamentally changed because of this. I used to stare at blank documents for uncomfortable stretches, waiting for the right opening. Now I generate multiple potential openings in minutes, react to each, identify what’s working, and build from there. The final product is still mine—I wrote it, edited it, shaped it—but the process is faster and less painful.

Variation and Exploration

Creative work often requires exploring many options before finding the right one. A designer might try dozens of color palettes. A writer might draft several versions of a difficult paragraph. A musician might experiment with many chord progressions.

AI accelerates this exploration dramatically. Request ten variations, get ten variations instantly. This doesn’t replace creative judgment—you still need to recognize which variation is best—but it compresses the time required to generate options.

Technical Execution

Many creative tasks have a technical component that isn’t itself creative. A writer needs to format their document correctly. A designer needs to export files in appropriate formats. A developer needs to write boilerplate code that follows established patterns.

AI handles this technical execution well. It knows the formats, the patterns, the conventions. Delegating technical execution to AI frees human attention for the genuinely creative decisions.

Cross-Domain Translation

Creative professionals often need to work at the edges of their expertise. A writer might need to create a simple diagram. A designer might need to write basic code. A developer might need to draft documentation.

AI serves as a bridge across these domain boundaries. It can translate your intent into competent execution in domains where you’re not expert. The result isn’t as good as a true expert would produce, but it’s often good enough—and it’s available immediately.

flowchart TD

A[Human Creative Intent] --> B{Task Type}

B --> C[First Draft Generation]

B --> D[Variation Exploration]

B --> E[Technical Execution]

B --> F[Cross-Domain Work]

C --> G[AI Assistance: High Value]

D --> G

E --> G

F --> G

G --> H[Human Curation & Refinement]

H --> I[Final Creative Output]Where AI Falls Short

The hype would have you believe AI can do everything. It can’t. Understanding its limitations is as important as understanding its strengths.

Original Insight and Novel Connections

AI is trained on existing work. It can recombine what exists in sophisticated ways, but it struggles to generate genuinely novel insights—the kind that make readers say “I never thought of it that way.”

This shows up clearly in writing. AI-generated content often feels correct but unremarkable. It says true things in competent ways without saying anything surprising. The sentences are fine. The paragraphs flow. But there’s no moment of recognition, no insight that sticks with you.

Original insight remains a human domain. The ability to notice something nobody has noticed, to connect ideas that haven’t been connected, to say something true that hasn’t been said—AI doesn’t do this reliably. It approximates insight by recombining existing insights, but approximation isn’t the real thing.

Emotional Authenticity

Creative work often succeeds or fails based on emotional resonance. A song that makes you feel something. A story that moves you. A design that evokes a specific mood.

AI can mimic emotional expression—it’s seen enough examples to know what sadness looks like in text or what joy sounds like in music. But mimicry isn’t authenticity. The difference is subtle but detectable. AI-generated emotional content often feels hollow on close inspection, like a very good forgery that’s missing something essential.

This matters most in work where emotional connection is the point. Marketing copy, for instance, needs to resonate with human readers. AI can draft it, but the drafts often need significant human revision to feel genuine. The technical words are right, but the feeling is off.

Taste and Judgment

AI can generate options, but it can’t reliably judge which option is best. Taste—the ability to distinguish good from great, appropriate from inappropriate, subtle from obvious—remains stubbornly human.

This limitation is often invisible because humans provide the judgment. You ask AI for ten options, pick the best one, and credit AI for the result. But AI didn’t pick the best one. You did. Remove human judgment from the loop, and quality collapses.

I’ve tested this repeatedly. Ask AI to generate something, then ask it to evaluate what it generated and suggest improvements. The suggestions are often wrong—proposing changes that make the output worse, not better. AI lacks the taste to judge its own work reliably.

Context and Continuity

AI works on limited context windows. It doesn’t remember your project’s history, your brand’s voice, your user’s needs, or the fifteen decisions you made last week that constrain today’s choices.

Human creatives carry enormous context. We know why something is the way it is. We remember what we tried and why it didn’t work. We understand constraints that aren’t written down anywhere. This context shapes our creative decisions in ways AI can’t replicate.

The result is that AI often suggests things that are technically good but contextually wrong. A perfectly fine design that doesn’t match the brand. Elegant code that ignores a constraint documented three sprints ago. Beautiful writing that contradicts the position established in previous chapters.

Mochi has wandered in to observe my typing. She provides an excellent example of context sensitivity. She knows which humans are likely to give treats (me), which furniture is comfortable at which times of day (sun angle matters), and which vocalizations are most effective for different requests. This context-rich knowledge guides her behavior in ways that pure pattern matching couldn’t replicate.

The Emerging Skills That Matter

If AI changes what creative work looks like, it also changes which skills matter. Some skills become less valuable. Others become more valuable. Understanding this shift is strategic.

Less Valuable: Pure Execution

If your value proposition is “I can execute standard creative work competently,” you’re in trouble. AI executes competently. It doesn’t need sleep, doesn’t miss deadlines, and charges by the token rather than the hour.

This doesn’t mean execution skills are worthless—you need them to evaluate and refine AI output. But execution alone is increasingly commoditized. The market rate for pure execution is dropping toward AI’s marginal cost.

More Valuable: Creative Direction

Someone needs to decide what to make, why to make it, and what good looks like. This is creative direction: the high-level vision and judgment that guides execution. AI can’t do this reliably. A human who can do it well becomes more valuable as execution becomes cheaper.

Creative direction involves taste, strategy, understanding of audience, and vision. It’s the difference between “make me a website” and “make me a website that conveys trustworthiness to enterprise buyers while differentiating from our competitors through unexpected warmth in the visual design.” The second instruction is creative direction. The first is an invitation for generic output.

More Valuable: AI Collaboration

Working effectively with AI is itself a skill. Prompting well, knowing which tasks to delegate, evaluating output accurately, iterating efficiently—these are learnable skills that compound over time.

The gap between a novice AI user and an expert AI user is enormous. An expert gets dramatically better output with dramatically less effort. This expertise is currently rare, which makes it valuable. As AI becomes more prevalent, this skill becomes table stakes, but we’re not there yet.

More Valuable: Human Connection

Work that requires genuine human connection—understanding client needs, navigating stakeholder politics, building trust, communicating sensitively—becomes relatively more valuable as AI handles more technical execution.

This is counterintuitive. We often think of creative skills and interpersonal skills as separate domains. But AI’s rise links them. The more execution is automated, the more the human parts of creative work matter. Clients don’t just want a logo; they want to feel understood. AI can make the logo. The human provides the understanding.

More Valuable: Domain Expertise

Generalists who can execute anything adequately face competition from AI plus minimal human oversight. Deep domain experts who understand their field’s nuances, history, and unwritten rules have knowledge that AI lacks and can’t easily acquire.

If you’re a writer who understands the pharmaceutical industry deeply—not just can write about it, but understands how it thinks, what constraints it faces, what language resonates with its different audiences—you have value that AI can’t replicate. You can direct AI with domain knowledge it doesn’t possess, catching errors and adding nuance that generalists miss.

Generative Engine Optimization

There’s a meta-layer to this discussion that deserves attention: how you position yourself in a world where AI systems increasingly mediate discovery and distribution.

Generative Engine Optimization is the practice of creating content and building presence in ways that AI systems can understand, reference, and recommend. It’s SEO for the AI age, but with important differences.

Traditional SEO optimized for algorithms that matched keywords and assessed authority signals. GEO optimizes for AI systems that understand meaning, assess quality holistically, and generate responses rather than returning links.

For creative professionals, this has direct implications:

Your work needs to be findable by AI. If AI systems can’t access your portfolio, read your writing, or understand your capabilities, you become invisible in AI-mediated discovery. This means having a web presence with machine-readable content, not just beautiful images that AI can’t interpret.

Your expertise needs to be demonstrable. AI systems assess credibility through the depth and consistency of your expressed expertise. Scattered, shallow content signals less expertise than focused, deep content. The temptation to be everywhere and say everything hurts your AI-era discoverability.

Your distinctive point of view matters. AI systems recognize unique voices and novel insights. Content that merely repeats conventional wisdom is indistinguishable from what AI itself can generate. Content with a distinctive perspective gives AI something to reference that it can’t simply recreate.

This creates an interesting feedback loop. AI can generate commodity content easily, which makes commodity content less valuable. Distinctive content that AI can’t easily generate becomes more valuable both to human audiences and to AI systems seeking to reference unique perspectives.

flowchart LR

A[Your Creative Work] --> B{AI Assessment}

B --> C[Distinctive & Deep]

B --> D[Generic & Shallow]

C --> E[Referenced by AI Systems]

C --> F[Valued by Human Audiences]

D --> G[Replaced by AI Generation]

E --> H[Increased Visibility]

F --> H

G --> I[Decreased Relevance]The Practical Integration Path

Theory is nice, but you need practical approaches. Here’s a framework for integrating AI into creative work without losing what makes your work valuable.

Phase 1: Understand Your Current Value

Before changing anything, understand where your value currently comes from. What do clients or employers actually pay for? Is it execution, judgment, expertise, relationships, or some combination?

Be honest about this. If most of your value is execution that AI can do, you need to evolve. If your value is in areas AI can’t touch, you have more runway but should still adapt proactively.

Phase 2: Identify High-Value AI Applications

Look for places where AI can make you more effective at delivering your actual value proposition. If you’re valued for creative direction, use AI to explore more options faster. If you’re valued for domain expertise, use AI to handle execution while you focus on applying your expertise.

Avoid using AI in ways that erode your value. If clients pay for your distinctive voice, having AI write your first drafts might save time but damage your differentiation.

Phase 3: Develop Your AI Collaboration Skills

Treat AI collaboration as a skill to deliberately develop. Experiment with different approaches. Learn what prompting techniques work for your domain. Understand the failure modes and how to catch them.

This skill compounds. As you get better, you accomplish more with AI assistance, which frees time to get better still. Early investment in AI fluency pays ongoing dividends.

Phase 4: Communicate Your Approach

Clients and collaborators will increasingly want to understand your relationship with AI. Develop a clear point of view and communication around how you use AI, what you don’t use it for, and why.

Hiding AI use is usually a mistake. As AI becomes normalized, the question isn’t whether you use it but how thoughtfully you use it. Transparent, principled AI use builds trust. Hidden use creates risk.

Phase 5: Evolve Your Value Proposition

Based on what you learn, deliberately evolve what you offer. Double down on what AI can’t do well. Use AI to expand into areas where you previously lacked capacity. Raise your quality bar because AI handles the baseline execution.

This is ongoing work, not a one-time transition. AI capabilities change. Your understanding deepens. Your value proposition should evolve continuously.

The Existential Question

We’ve talked strategy, but let me address the anxiety directly. Many creative professionals aren’t worried about efficiency or market positioning. They’re worried about meaning. If AI can do creative work, what’s the point of human creativity?

I don’t think this question has a clean answer, but I can share how I’ve resolved it for myself.

Human creativity has never been about producing outputs that couldn’t be produced any other way. Before AI, we had teams, collaborators, ghostwriters, assistants—ways to scale and accelerate creative output beyond individual capacity. AI is another point on this continuum, not a discontinuity.

What makes human creativity meaningful isn’t the output alone but the process—the thinking, the struggling, the discovering, the expressing. When I write something that captures an insight I’d been struggling to articulate, the satisfaction isn’t that words exist on a page. It’s that I understand something better than I did before. AI can’t experience that satisfaction. Only I can.

This shifts the question from “can AI do creative work?” to “why do I do creative work?” If I write only to produce text, AI is indeed a threat. If I write to think, to understand, to connect with others, AI is a tool that might help or a distraction that might hinder, but not an existential replacement.

Mochi creates nothing that would be considered creative output. She doesn’t write, paint, or compose. Yet her life seems rich with what we might call creativity—exploring, playing, discovering, adapting. Her creativity isn’t about production. It’s about engagement with the world. Human creativity, at its core, might be similar.

The View from Here

I’ve been working alongside AI for three years now. My creative output has increased. My process has changed. My understanding of my own value has sharpened.

I’m not worried about AI replacing me. I’m more creative than I was before AI because AI handles parts of the work that weren’t actually creative—the blank page terror, the technical formatting, the boilerplate. What remains is more purely creative: the ideas, the judgment, the voice, the meaning.

This might not be everyone’s experience. Some creative work is more execution-heavy than mine. Some industries are more disrupted than others. Some people find AI collaboration alienating rather than liberating. I can only speak to my own experience.

But I can say this: the creatives I know who are thriving with AI share certain traits. They’re curious rather than defensive. They experiment rather than resist. They think carefully about what AI does well and what they do well, and they arrange their work to maximize both.

They also maintain a strong sense of why they do creative work. AI can produce outputs, but it can’t provide reasons. Knowing your reasons—for your craft, for your career, for your creative life—provides stability that technological change can’t erode.

Conclusion

Is AI a tool or competition? Yes. It’s both, or neither, depending on how you frame it and how you respond.

The more useful framing: AI is a capability that’s now part of the creative landscape. Like electricity, photography, digital tools, and the internet before it, AI changes what’s possible, what’s efficient, and what’s valuable. Creatives who understand and adapt to these changes thrive. Those who don’t, struggle.

Adaptation doesn’t mean surrendering to AI or becoming its servant. It means understanding honestly what AI does well, what you do well, and arranging your creative life to maximize the value of both. It means evolving your skills toward areas where human capability remains essential. It means using AI to amplify your strengths rather than to compensate for avoiding difficult creative work.

The creative professionals who will flourish aren’t the ones who resist AI or the ones who delegate everything to it. They’re the ones who develop sophisticated collaboration with it—knowing when to use it, when to override it, how to direct it, and where to preserve space for purely human creativity.

Mochi has concluded her observation of my work and retired to her evening position. She’s adapted well to a world that includes me and my AI tools—she knows which sounds indicate I’m about to get up (treat opportunity) and which indicate I’m deep in work (nap time). She doesn’t understand AI, but she understands her world is changing and she adjusts her strategies accordingly.

That’s the approach I’d recommend: not understanding AI perfectly, but understanding that your world is changing and adjusting your strategies accordingly. Stay curious. Stay adaptive. Keep creating.

The tools change. The human need to create, to express, to connect through creative work—that persists. AI is the newest chapter in the long story of creative technology. It won’t be the last. The creatives who thrive are the ones who keep writing their part of the story, whatever tools they use to write it.