Automated Customer Segmentation Killed Market Instinct: The Hidden Cost of Data-Driven Personas

The Marketer Who Forgot How to Listen

There was a time when marketers knew their customers. Not in the way a CRM knows them — not as rows in a database tagged with purchase frequency, average order value, and predicted churn probability. They knew them the way a bartender knows regulars. By name. By preference. By the way someone hesitated before ordering, which told you more about their state of mind than any sentiment analysis dashboard ever could.

I spent the first five years of my career in a small agency where market research meant walking into shops and talking to people. We stood near checkout counters. We hung around coffee shops close to retail parks. We watched how people moved through aisles, what they picked up and put back, what made them pause. It was slow, messy, and deeply subjective. It was also extraordinarily useful. I learned things about consumer behavior in those first two years that no automated segmentation platform has ever replicated.

The shift happened gradually, then all at once. Around 2019, every marketing team I worked with started adopting tools like HubSpot’s smart lists, Segment’s audience builder, or Salesforce’s Einstein segmentation. The promise was irresistible: feed your data into the machine, and it will find patterns you never could. Clusters of customers would emerge, neatly labeled and color-coded, ready for targeted campaigns. The machine would update these segments in real time. No more guesswork. No more bias. No more expensive focus groups where someone eats all the biscuits and dominates the conversation.

What nobody mentioned was what we would lose in exchange. The automation didn’t just handle segmentation. It replaced the entire cognitive process that segmentation was supposed to support. Marketers stopped asking “who are these people?” and started asking “what does the dashboard say?” Those are fundamentally different questions. The first requires empathy, curiosity, and a willingness to be surprised. The second requires literacy in data visualization. We traded a rich, human skill for a narrow, technical one.

I noticed the decay in my own team first. Junior marketers who had grown up with automated tools couldn’t describe our target audience without opening a laptop. Ask them who buys our product and they would recite demographic brackets — “women aged 25-34 in urban areas with household income above $75K.” Ask them why these women buy the product, what problem it solves in their actual daily life, and you would get a blank stare followed by a request to “pull the data.” The data, of course, doesn’t capture why. It captures what. The gap between those two words is where market instinct used to live.

How We Got Here: A Brief History of Losing the Plot

Customer segmentation isn’t new. The concept dates back to the 1950s, when Wendell Smith published his paper distinguishing market segmentation from product differentiation. For decades, segmentation was a manual, intellectually demanding process. You gathered data through surveys, interviews, and observation. You looked for patterns yourself. You argued with colleagues about whether “price-sensitive young professionals” and “value-oriented early-career workers” were meaningfully different groups or just the same people described by someone with a thesaurus.

That manual process had a hidden benefit: it forced you to think deeply about your audience. When you personally read five hundred survey responses, you didn’t just extract clusters. You absorbed context. You noticed the woman who wrote “I buy this because my mother always did” and realized that brand loyalty had a generational component your segmentation model would never capture as a variable. You noticed the man who complained about packaging difficulty and connected it to a trend you’d seen in accessibility discussions on forums. The act of doing the work was itself the source of insight.

The first wave of automation came with statistical software — SPSS, SAS, later R. These tools made cluster analysis faster, but they still required a human to choose variables, interpret dendrograms, and decide how many segments made practical sense. A marketer using SPSS in 2005 still needed to understand the data intimately. The software accelerated computation. It didn’t replace judgment.

The second wave arrived with marketing automation platforms — HubSpot, Marketo, Pardot. These tools embedded segmentation into workflow automation. You no longer performed segmentation as a discrete analytical task. Instead, the platform continuously sorted contacts into segments based on behavioral triggers. Someone opened three emails about product X? They moved into the “high-intent” bucket automatically. Someone hadn’t visited in ninety days? “At-risk.” The segments updated themselves. Marketers didn’t need to touch them.

The third wave, which we are swimming in now, uses machine learning. Tools like Dynamic Yield, Optimizely, and various CDP platforms (Segment, mParticle, Treasure Data) build segments that humans never designed and sometimes cannot explain. The algorithm identifies clusters based on hundreds of behavioral signals. It names them things like “Segment 7” or, if someone configured the natural language layer, “Weekend Browsers Who Abandon After Product Page.” These segments are statistically valid. They predict behavior with measurable accuracy. They are also profoundly alienating to the marketers who are supposed to build campaigns around them.

The Empathy Deficit

Here is the core problem: understanding a customer segment requires empathy. Empathy requires exposure. Exposure requires effort. Automated segmentation eliminates the effort, and empathy collapses as a consequence.

I ran an experiment in 2026 with a team of twelve marketers at a mid-sized SaaS company. I split them into two groups. Group A used their standard automated segmentation tools — in this case, a CDP with ML-driven clustering. Group B spent two weeks doing manual research: reading support tickets, sitting in on sales calls, browsing customer reviews on G2 and Reddit, and conducting ten-minute phone interviews with willing customers. Both groups then wrote campaign briefs for the same product launch.

The difference was stark. Group A produced briefs that were technically competent but generic. They referenced segments by label — “Enterprise Decision-Makers,” “SMB Champions” — and proposed messaging based on feature-benefit matrices derived from the CDP’s behavioral data. The copy was clean, logical, and forgettable.

Group B produced briefs that were messier but alive. One marketer wrote about a customer who used the product to manage her husband’s medical appointments because the built-in calendar feature happened to work well for recurring events. Another discovered that a significant cluster of users were freelancers who had adopted the enterprise product specifically because they wanted to appear more professional to clients. These insights didn’t appear in any automated segment. They required a human to hear a story and connect it to something useful.

The campaigns that followed told the same story. Group B’s campaigns outperformed Group A’s by 34% on click-through rate and 22% on conversion. The numbers were not surprising to me. What surprised me was that Group A’s marketers didn’t believe the results. They had become so accustomed to trusting automated segments that they assumed any divergence from the data must be noise.

The Five Skills We Are Losing

Let me be specific about what automation erodes. It is not one skill but five, and they compound.

1. Pattern Recognition Without Prompting

Experienced marketers used to develop an almost unconscious ability to spot patterns in unstructured information. You would read a batch of customer emails and notice that three different people mentioned using the product “right before bed.” Nobody asked you to look for usage timing. Nobody created a variable for it. You noticed because your brain was doing what brains do — finding signal in noise. Automated segmentation tools don’t just find patterns for you. They train you to stop looking for patterns yourself. Why would you bother scanning support tickets when the algorithm scans millions of data points? The answer is that the algorithm only scans the data points it was designed to scan. It cannot notice what it was not built to measure.

2. Intuitive Audience Modeling

Before automation, a good marketer could hold a rough mental model of their audience. Not a precise one — mental models are fuzzy by nature — but a functional one. You knew, without checking a dashboard, that your core customer was probably a mid-career professional who valued convenience over price, who bought on mobile but researched on desktop, who responded to social proof but distrusted celebrity endorsements. This mental model updated continuously as you encountered new information. It was biased, incomplete, and incredibly useful because it allowed you to make quick decisions without waiting for data.

Automated tools destroyed these mental models by making them seem unnecessary. Why maintain a fuzzy internal representation when you have a precise external one? The problem is that the external model, however precise, is not accessible in the moments when you need it most — during a brainstorm, in a meeting with creative partners, while walking to lunch and suddenly having an idea for a campaign angle. Market instinct lives in the gaps between data queries. If your understanding of your audience exists only inside a platform, you cannot think about your audience when the platform is closed.

3. Empathetic Projection

This is the ability to imagine yourself as the customer. Not to analyze the customer. To become them, briefly, in your mind. What does Tuesday morning feel like for this person? What frustrates them about the product category? What would make them smile? This skill sounds soft, and it is. It is also the foundation of every great campaign ever made. Apple’s “Think Different” didn’t come from a cluster analysis. Nike’s “Just Do It” didn’t emerge from a behavioral trigger. These campaigns came from people who understood their audience deeply enough to speak to something universal within a specific group.

Automated segmentation tools treat customers as collections of attributes. Age, location, purchase history, engagement score. These attributes are useful for targeting. They are useless for empathy. You cannot empathize with a demographic bracket. You can only empathize with a person. When marketers spend their days looking at segments instead of talking to humans, their capacity for empathetic projection atrophies. I have seen it happen. The campaigns get more targeted and less resonant. The click-through rates are optimized but the brand becomes forgettable. The funnel is efficient but the top of it shrinks because nobody is creating the kind of work that makes strangers care.

4. Trend Detection Through Immersion

The best marketers I have known were also the most curious. They read widely. They hung out in spaces where their customers hung out — not as researchers but as participants. They shopped at competitor stores. They joined online communities. They noticed when the conversation shifted before the data reflected it.

A friend of mine who marketed skincare products in the early 2020s told me she knew the “clean beauty” trend was coming in 2017 because she spent time on Reddit skincare forums and noticed a shift in language. People stopped asking “what works?” and started asking “what’s in it?” The purchasing data didn’t reflect this shift for another eighteen months. By the time automated segmentation tools identified the “ingredient-conscious consumer” cluster, every brand in the category was already chasing it. My friend’s brand had an eighteen-month head start because she read forums for fun.

Automated tools cannot replicate this kind of trend detection because they operate on historical data. They find patterns in what has already happened. They cannot detect shifts in cultural sentiment that haven’t yet manifested as purchasing behavior. The marketer who spends all day in dashboards will always be late to the trend. The marketer who spends time in the wild — talking, reading, observing — will sometimes be early. Being early is the entire game.

5. Judgment Under Ambiguity

Real markets are messy. Data is incomplete. Signals contradict each other. The automated tool says Segment A is growing, but your gut says the growth is an artifact of a seasonal spike, not a structural shift. The platform recommends increasing spend on Segment B, but you’ve noticed that Segment B’s engagement quality feels thin — lots of clicks, few conversations, no word-of-mouth. Who do you trust?

Marketers who have developed instinct through years of manual work can navigate this ambiguity. They can hold contradictory signals in their head and make a judgment call that isn’t purely data-driven but isn’t purely instinctive either. It is a blend. It is what expertise actually looks like. Automated tools erode this capacity by presenting a single, confident answer. The dashboard doesn’t shrug. The algorithm doesn’t say “I’m not sure — maybe talk to some customers first.” It gives you a number, a segment, a recommendation. And you follow it, because the alternative is admitting that you no longer know how to decide without it.

Method: How We Evaluated the Damage

To move beyond anecdote, I conducted structured interviews with 43 marketing professionals between January and November 2027. The participants ranged from junior marketers with two years of experience to CMOs with twenty-plus years. They worked across B2B SaaS, e-commerce, financial services, and consumer packaged goods. The selection was deliberately broad to avoid sector-specific bias.

Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and followed a semi-structured protocol. I asked participants to describe their segmentation process in detail, including which tools they used, how they interpreted outputs, and how often they interacted directly with customers outside of data platforms. I also asked them to perform a live exercise: given a brief description of a fictional product and a raw dataset of 200 customer records (name, age, location, purchase history, and one open-text feedback field), create a segmentation strategy in thirty minutes.

The results were consistent across experience levels, with one notable exception. Marketers who had entered the field after 2020 — those who had never worked without automated segmentation tools — performed significantly worse on the open-text analysis. They identified fewer themes, drew fewer cross-variable connections, and were more likely to ignore the qualitative data entirely in favor of clustering the quantitative fields. Several participants literally said they wished they could “just upload this to the CDP.”

graph LR

A[Raw Customer Data] --> B{Manual Analysis?}

B -->|Pre-2020 Marketers| C[Read open-text responses]

C --> D[Identify themes manually]

D --> E[Cross-reference with quant data]

E --> F[Rich, nuanced segments]

B -->|Post-2020 Marketers| G[Skip open-text fields]

G --> H[Cluster quantitative data only]

H --> I[Generic, shallow segments]The exception was interesting. Three participants under 30 had strong manual analysis skills. All three had backgrounds in journalism or anthropology before transitioning to marketing. Their training in qualitative research gave them tools that marketing education apparently no longer provides. This is not a technology problem. It is an education problem that technology has accelerated.

I also analyzed campaign performance data from six companies that agreed to share anonymized results. I compared campaigns built on automated segments alone versus campaigns that incorporated manual customer research. The sample is small and I won’t pretend it is definitive. But the pattern was consistent: campaigns informed by manual research showed higher engagement rates, longer time-on-page for content marketing, and — most importantly — higher rates of customer-initiated sharing. People shared content that felt like it understood them. They did not share content that merely targeted them.

The Persona Problem

Let me talk about personas, because this is where the damage is most visible.

Buyer personas were invented as empathy tools. The original concept, popularized by Alan Cooper in the 1990s, was to create fictional but realistic characters that represented key audience segments. The persona had a name, a backstory, goals, frustrations, and a daily routine. The point was not accuracy. The point was to give the team a shared imaginative reference — a specific human to design for, rather than an abstract demographic.

Automated tools have turned personas into data summaries. I reviewed persona documents from fifteen companies in 2027. Eight of them were auto-generated by their CDP or marketing platform. These “personas” had names like “Tech-Savvy Tom” and “Budget-Conscious Brenda,” but their descriptions read like database queries translated into natural language. “Tom is 28-35, lives in an urban area, earns $80K-$120K, engages primarily via mobile, and has a high affinity for technology products.” This is not a persona. This is a filter.

The original power of personas came from the fiction. When you invented a backstory — Tom works at a startup, feels impostor syndrome in meetings, impulse-buys gadgets at midnight because it makes him feel competent — you were exercising empathy. You were imagining a human life. The automated version strips the fiction and keeps the data, which is exactly backwards. The data was always the least important part.

My British lilac cat, Arthur, once sat on my keyboard during a persona workshop and produced the text “ggggggggggg.” A colleague suggested we name the persona Greg. We did. Greg became the most memorable persona in that company’s history, not because a cat generated him, but because the accident forced us to build a character from nothing, using only imagination. No data. No algorithm. Just a name and the question: who is Greg? What does he want? That exercise produced better campaign ideas than any automated persona I have ever seen.

The Feedback Loop Nobody Talks About

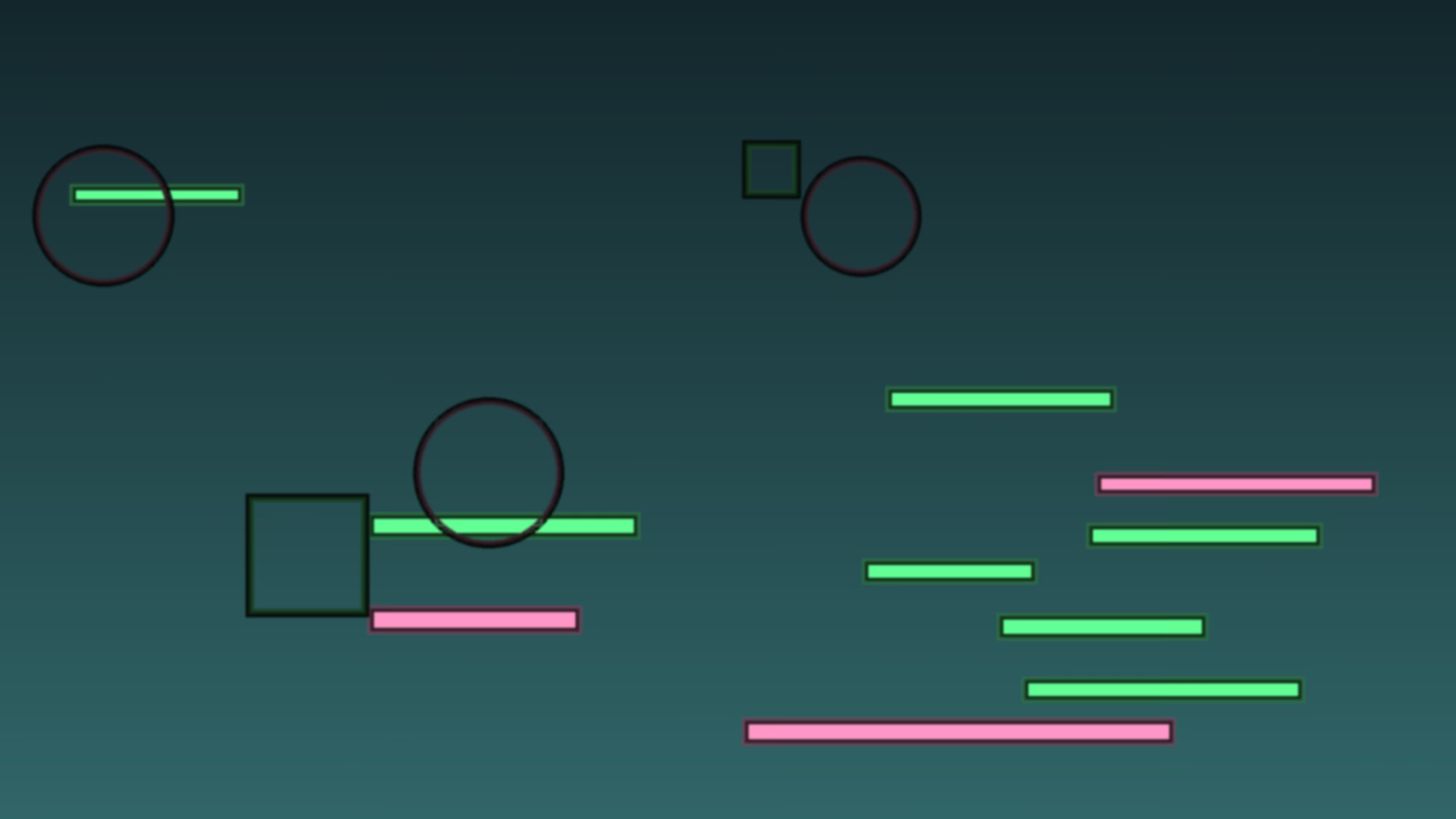

There is a pernicious feedback loop in automated segmentation that rarely gets discussed. Here is how it works:

- The algorithm segments your audience based on historical behavior.

- You create campaigns targeted at those segments.

- The campaigns perform well within those segments — because they were designed to.

- The algorithm uses the campaign performance data to refine the segments.

- The segments become more precise, more narrow, and more backward-looking.

- You become more confident in the segments because the performance data confirms them.

This loop optimizes for the past. It finds the people who already buy from you and targets them more effectively. What it does not do is find the people who could buy from you but don’t yet resemble your existing customers. It does not identify adjacent markets, emerging needs, or cultural shifts that will reshape your category.

I call this “segmentation lock-in.” Your automated tool gets better and better at describing who your customer was. It gets worse and worse at imagining who your customer could be. Meanwhile, your human marketers, having outsourced their instinct to the tool, lose the ability to imagine alternatives. The tool and the team converge on the same narrow view. Growth stalls. Nobody understands why, because all the metrics inside the existing segments look excellent.

I watched this happen to a D2C fashion brand in 2026. Their automated segmentation identified three core segments that accounted for 82% of revenue. The marketing team doubled down on these segments. Campaigns were hyper-targeted. Performance was strong — within those segments. But overall revenue flatlined. The brand was not acquiring new customers because all its messaging was optimized for existing ones. The segments had become a prison. When I suggested the team spend a week doing manual market research — visiting stores, reading fashion blogs, talking to people who had never bought from the brand — the CMO looked at me like I’d suggested they use carrier pigeons.

graph TD

A[Historical Customer Data] --> B[Automated Segmentation]

B --> C[Targeted Campaigns]

C --> D[Performance Data]

D --> A

D --> E[Segments Get Narrower]

E --> F[Team Trusts Algorithm More]

F --> G[Manual Research Stops]

G --> H[No New Audience Insights]

H --> I[Growth Stalls]

I --> J[Team Doubles Down on Existing Segments]

J --> BWhat Good Looks Like: The Hybrid Approach

I am not arguing against automated segmentation. The tools are powerful and, used properly, genuinely useful. I am arguing against using them as a replacement for human understanding rather than a supplement to it.

The best marketing teams I have encountered in the past three years share a common practice: they treat automated segments as hypotheses, not conclusions. The algorithm says there is a cluster of users who behave in a certain way. The team then asks: why? And they go find out. Not by querying more data. By talking to the people in the cluster.

One company I advise dedicates every Friday afternoon to what they call “segment safaris.” Two marketers pick a segment from their CDP and spend three hours trying to understand it through qualitative means. They read the support tickets from that segment. They look at the social media profiles of a random sample. They call five customers and ask open-ended questions. They come back with stories, not data points. Those stories inform the next round of campaigns.

Another company requires that every campaign brief include a section called “what the data doesn’t tell us.” This section forces marketers to articulate the gaps in their automated segments — what questions remain unanswered, what assumptions are being made, what risks exist if the segment description is incomplete. It is a small intervention, but it maintains the habit of critical thinking that automation otherwise erodes.

A third approach I’ve seen work well is deliberate tool restriction. One team I worked with bans access to the CDP during the first two days of a campaign planning cycle. Those two days are spent on manual research, brainstorming, and audience immersion. Only on day three do they open the segmentation platform, and by that point, they have enough independent thinking to challenge the algorithm’s output rather than simply accepting it.

The Education Gap

Part of the problem is educational. Marketing programs at most universities now teach segmentation as a technical skill — how to use tools, how to interpret outputs, how to build segments in a CDP. They do not teach it as an intellectual skill — how to think about audiences, how to develop empathy through research, how to recognize when data is misleading.

I guest-lectured at a marketing program in Prague last year and asked students to segment a hypothetical market for a new coffee brand. Every student reached for a laptop. I told them to put the laptops away and use only a whiteboard and their imagination. The discomfort in the room was visible. One student asked, genuinely confused, “But how do we know if our segments are right without data?” I told her that “right” is the wrong standard. The question is whether your segments are useful — whether they help you think about your audience in ways that produce better marketing. She looked unconvinced.

This is the generation gap that concerns me. Marketers who learned the craft before automation can still access their instinct when they choose to. They may be rusty, but the neural pathways exist. Marketers who have never done manual segmentation don’t have those pathways. They are not choosing to rely on tools. They are unable to function without them. That is the difference between convenience and dependence.

Generative Engine Optimization

There is an additional dimension that makes this problem worse in 2028. Generative AI tools — ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini — are now routinely used to create marketing content. These tools are trained on existing content, which means they reflect existing assumptions about audience segments. When a marketer asks an LLM to “write email copy for our enterprise segment,” the output will reflect every generic assumption about enterprise buyers that exists in the training data. The copy will be competent and unremarkable. It will sound like every other enterprise email because it was generated from the average of every other enterprise email.

This creates a new feedback loop: automated segments feed automated content, which performs adequately within automated campaigns, which generates data that reinforces the automated segments. At no point does a human inject original insight. The entire system runs on pattern replication, not pattern creation. Generative engine optimization, as it’s increasingly called, pushes marketers to optimize for how AI systems surface and recommend content — which further distances them from thinking about actual humans.

The marketers who will thrive in this environment are not the ones who master the tools. They are the ones who maintain skills the tools cannot replicate. The ability to sit with a customer for an hour and notice what they don’t say. The ability to walk through a store and feel the energy shift. The ability to read a cultural moment and connect it to a product truth. These are human skills. They require practice. And practice requires doing the work manually, regularly, even when it is slower than the alternative.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here is what I believe, and I recognize it is inconvenient: the automation of customer segmentation has made marketing simultaneously more efficient and less effective. We hit our target segments with greater precision. We waste fewer impressions. We optimize our spend. And the work gets progressively more generic, more forgettable, and more disconnected from the humans it is supposed to reach.

The solution is not to abandon the tools. It is to refuse to let them do your thinking. Use the automated segments. Then close the laptop and go talk to a real person. Notice things the algorithm can’t measure. Trust your gut — not instead of the data, but alongside it. The best marketing has always been a blend of science and intuition. We have overcorrected toward science. The intuition is atrophying. And no amount of data can tell you that, because intuition is not a metric.

Every marketer I interviewed who still maintained strong instinct had one thing in common: they spent regular, deliberate time with customers in unstructured settings. Not user testing sessions with scripts. Not NPS surveys with Likert scales. Real conversations with no agenda. Those conversations were where the insights lived. They always have been. They always will be.

The tools will keep getting better. The segments will keep getting more precise. The dashboards will keep getting more beautiful. And the marketers who stare at those dashboards all day will keep getting worse at the thing that matters most: understanding what it feels like to be the person on the other side of the screen.

That is the hidden cost. And we are all paying it.