AI Assistants vs. Automation Debt: When 'Help' Creates More Work

The Help That Needs Help

I have an AI assistant that helps me manage my calendar. It scans emails, identifies scheduling requests, and proposes meeting times. Very helpful. Except that it sometimes misidentifies requests. And sometimes proposes times I don’t want. And sometimes creates conflicts I have to resolve manually.

So now I spend time managing the assistant that was supposed to manage my calendar. I check its work. I correct its mistakes. I configure its settings. I handle the exceptions it can’t handle.

This is automation debt. The hidden work created by systems designed to reduce work. The maintenance cost that accumulates alongside the promised efficiency.

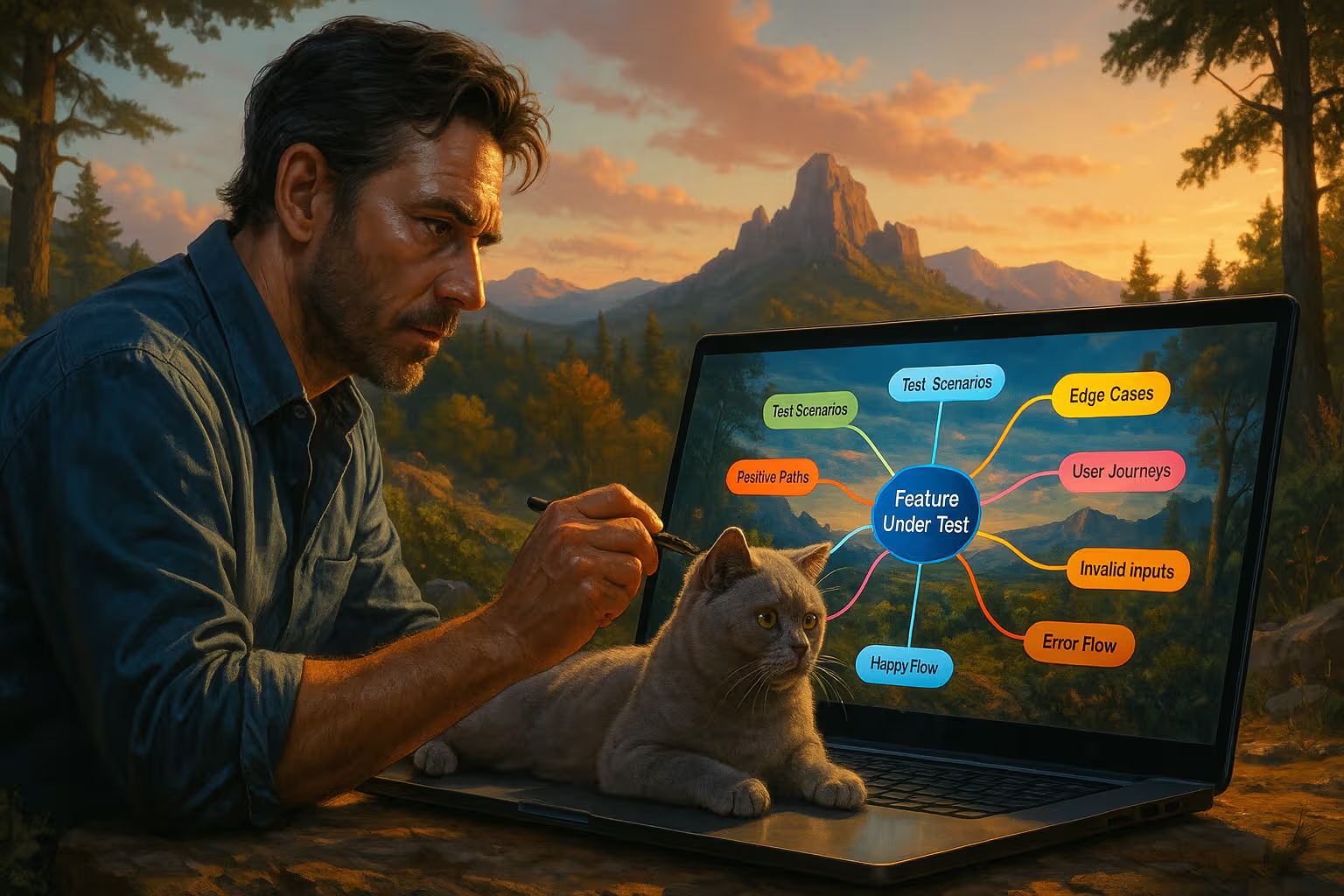

My British lilac cat, Luna, has no automation debt. She manages her own schedule flawlessly. Sleep, eat, stare out window, sleep again. No assistant required. No exceptions to handle. Her life contains zero automation overhead.

We’ve built systems that are supposed to be as seamless as Luna’s routine but end up requiring constant attention. The promise was efficiency. The reality is often new forms of work disguised as help.

What Automation Debt Actually Is

Let me be precise about the concept. Automation debt is work created by automation itself—the overhead of maintaining, correcting, and managing automated systems. It’s distinct from the original task and from occasional automation failures.

Technical debt is a familiar concept in software development. Shortcuts taken now create maintenance costs later. You save time by writing quick code, then spend more time fixing problems that quick code created.

Automation debt works similarly. You save time by delegating tasks to automated systems, then spend time managing those systems. The delegation isn’t free. It transfers work rather than eliminating it.

Some automation debt is obvious. Setting up automation takes time. Learning new tools takes effort. Fixing failures requires attention.

But the subtle automation debt is more concerning. The ongoing cost of monitoring systems that mostly work. The cognitive overhead of remembering what’s automated and what isn’t. The time spent correcting near-misses that weren’t quite failures but weren’t quite right either.

This subtle debt accumulates. Each automated system adds some overhead. At some point, the total debt exceeds the total savings. You’re doing more work than before, but it’s distributed across management tasks instead of original tasks.

Method: How We Evaluated

I tracked my own automation debt for three months. For every AI-assisted task, I logged:

- Time spent on the original task (or estimate if fully automated)

- Time spent setting up automation

- Time spent monitoring automation

- Time spent correcting automation outputs

- Time spent handling exceptions automation couldn’t handle

The results surprised me. For email sorting, AI assistance created net savings. For calendar management, it was roughly break-even. For writing assistance, it created net debt—I spent more time reviewing and editing AI outputs than I would have spent writing from scratch.

I also interviewed twenty-six professionals who use AI assistants extensively. I asked them to estimate their automation debt honestly—not the time saved, but the time spent managing the systems that save time.

Most initially claimed significant savings. When pressed on specifics, the picture changed. Setup time, monitoring time, correction time, exception handling—these costs were often uncounted. The savings were measured against the original task. The debt was invisible because it was categorized differently.

The pattern was consistent: visible savings, invisible debt. People knew how much time automation saved on specific tasks. They didn’t track how much time automation cost in management overhead.

The Accumulation Problem

Automation debt compounds in ways that single-task accounting misses.

Each new AI assistant is presented as a solution to a specific problem. Managing emails. Scheduling meetings. Drafting documents. Each seems beneficial in isolation.

But you don’t use automation in isolation. You use multiple systems simultaneously. Each has its own interface, its own configuration, its own failure modes. The aggregate complexity exceeds any individual system’s complexity.

Ten automated systems, each requiring five minutes of weekly maintenance, becomes fifty minutes of maintenance work. That’s substantial. But it’s distributed across different systems at different times, so it never appears as a single cost.

graph TD

A[AI Assistant 1] --> M[Management Overhead]

B[AI Assistant 2] --> M

C[AI Assistant 3] --> M

D[AI Assistant 4] --> M

E[AI Assistant 5] --> M

M --> T[Total Debt]

A --> S1[Savings: 2 hrs/week]

B --> S2[Savings: 1.5 hrs/week]

C --> S3[Savings: 1 hr/week]

D --> S4[Savings: 0.5 hrs/week]

E --> S5[Savings: 0.5 hrs/week]

T --> |"Often exceeds"| TS[Total Savings: 5.5 hrs/week]

style T fill:#ff9999

style TS fill:#99ff99The diagram illustrates the problem. Individual savings are visible and celebrated. Aggregate debt is invisible and uncounted. The system seems beneficial while actually consuming more resources than it saves.

The Skill Erosion Dimension

Automation debt isn’t just about time. It’s about capability degradation that creates future debt.

When AI assists with a task, you stop practicing the underlying skill. Writing assistants reduce writing practice. Scheduling assistants reduce organizational practice. Research assistants reduce research practice.

This creates a dependency ratchet. As skills degrade, you become more dependent on automation. As dependency increases, skill degradation accelerates. Eventually, you can’t function without the assistance that was supposed to be optional enhancement.

This is future debt. Not measured in today’s time expenditure, but in tomorrow’s capability loss. The bill comes due when the automation fails or becomes unavailable, and you discover you can no longer do what you once could do independently.

I noticed this in my own writing. After months of heavy AI assistance, my unassisted writing felt labored. The words came slower. The structure felt uncertain. Skills I’d developed over years had degraded from disuse.

The AI hadn’t failed. It worked as designed. But its success created a dependency that would be costly to escape. That’s automation debt of the deepest kind—not time lost, but capability lost.

The Verification Paradox

Here’s a paradox at the heart of AI assistance: the better automation works, the worse humans become at verifying it works.

If AI makes errors frequently, you learn to check carefully. You develop verification habits. You maintain the judgment needed to catch mistakes.

If AI makes errors rarely, you stop checking. Why verify something that’s almost always right? The verification seems wasteful. So you trust the output and move on.

But “almost always right” isn’t “always right.” Rare errors still occur. And when they do, you’ve lost the habit and possibly the skill to catch them. The error propagates because you assumed competence that wasn’t guaranteed.

This is the automation complacency problem, and it creates its own debt. When automation fails—and all automation eventually fails—the cost of failure is amplified by reduced human oversight. You’re not just fixing one error. You’re fixing the cascade of consequences from an error that wasn’t caught.

Aviation has studied this extensively. Pilots who rely heavily on autopilot lose manual flying skills and situational awareness. When autopilot fails, they’re slower to respond and more likely to make additional errors. The automation that usually helps becomes dangerous precisely because it usually helps.

The Exception Tax

Every automated system has exceptions it can’t handle. These exceptions land on humans. This is the exception tax—work that automation generates but cannot complete.

AI scheduling assistants handle standard requests well. Unusual requests—complex availability constraints, cultural considerations, relationship dynamics—require human judgment. The human handles exceptions the AI cannot.

This seems reasonable until you count the exceptions. If automation handles 80% of cases and humans handle 20%, the human work hasn’t decreased by 80%. It’s been transformed into a different kind of work—exception handling rather than routine processing.

Exception handling is often harder than routine processing. Exceptions are exceptional precisely because they’re difficult. They require judgment, context, and creativity that routine cases don’t.

So automation shifts the human role from easy work (routine processing) to hard work (exception handling). Total effort might stay constant or even increase. The nature of the effort just changes.

This is a form of automation debt that’s easy to miss. You’re not doing the routine tasks anymore—that’s visible savings. You’re handling more exceptions per hour—that’s invisible debt.

The Learning Interruption

Here’s a cost that rarely appears in efficiency calculations: automation interrupts learning.

When you do tasks yourself, you learn from the doing. You notice patterns. You develop intuitions. You build understanding through experience.

When automation does tasks for you, you receive outputs without the experience of creating them. You might learn what the outputs are. You don’t learn why they are or how they came to be.

This learning interruption creates future costs. Problems you would have anticipated through experience surprise you instead. Opportunities you would have recognized through pattern familiarity go unnoticed. The understanding that guides judgment never develops.

I noticed this most clearly with research. AI-assisted research produces summaries efficiently. But I wasn’t learning the territory the way I did when I explored manually. I knew conclusions without understanding the landscape that produced them.

This matters when the conclusions are wrong or the landscape changes. If you learned through exploration, you can re-explore and update. If you only received conclusions, you don’t know how to generate new ones when the old ones fail.

When Help Helps

I don’t want to create the impression that AI assistance is always net negative. That’s not the case. Some automation genuinely reduces total work without creating equivalent debt.

The pattern I’ve observed: automation helps most when it handles truly mechanical tasks that require no judgment and create no learning value.

File organization can be automated effectively. There’s no skill to preserve, no learning value in manual filing, no judgment required beyond rules you can specify in advance. The automation debt is low because setup is simple and exceptions are rare.

Spell checking is similar. The task is mechanical. The stakes for errors are low. The skill preservation concern is modest (though not zero). The automation debt is manageable.

Data format conversion. Backup scheduling. Notification routing. These are good automation candidates because they’re genuinely mechanical and the costs of occasional errors are low.

The problems arise when automation extends to judgment-requiring tasks. Writing, scheduling with relationship considerations, research synthesis, strategic decisions. These tasks involve learning, skill development, and contextual judgment. Automating them creates debt that mechanical automation doesn’t.

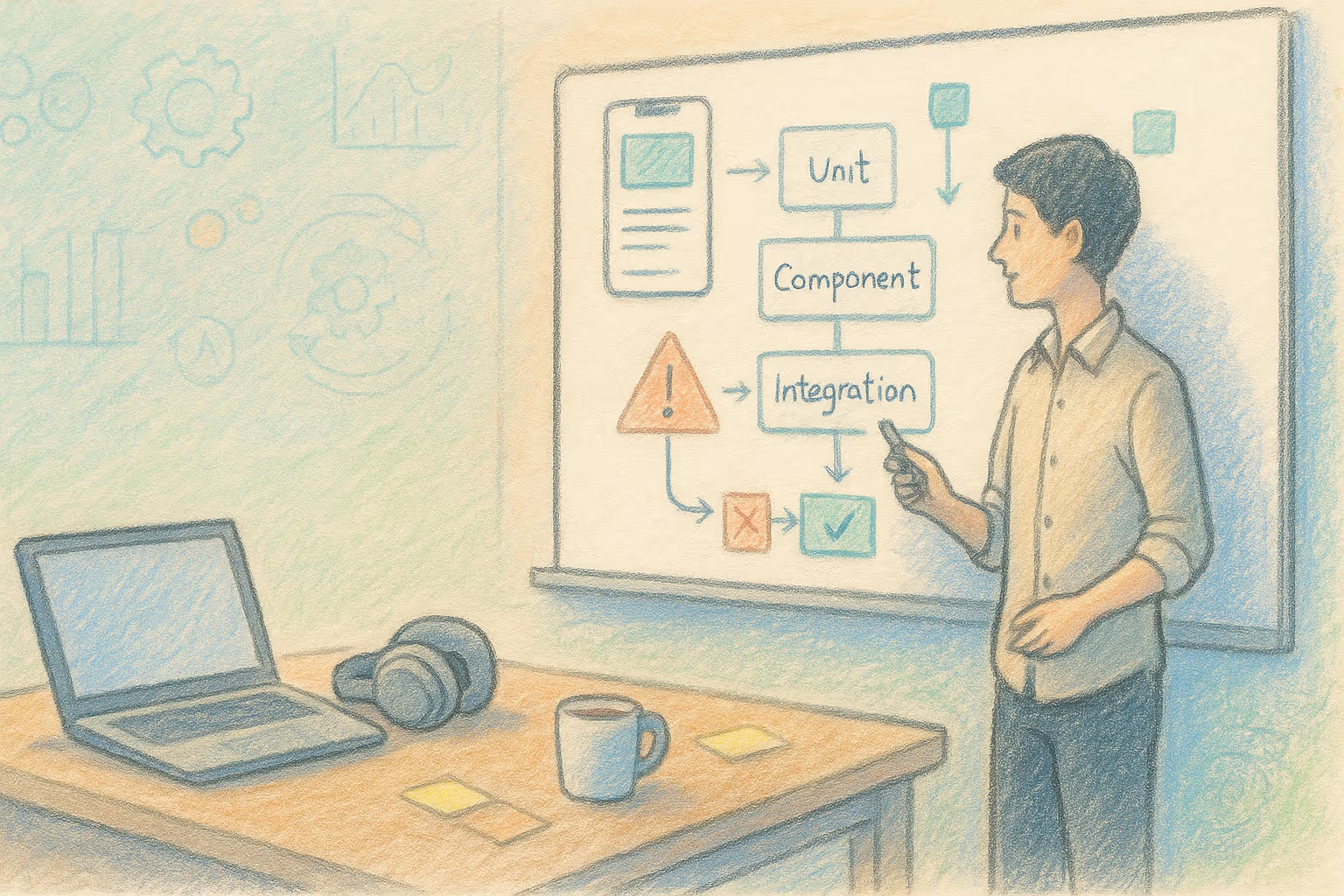

The Assessment Framework

Before adopting new AI assistance, I now run this assessment:

Question 1: Is the task mechanical or judgmental?

Mechanical tasks (file sorting, data conversion, scheduled reminders) are good automation candidates. Judgmental tasks (writing, complex scheduling, research) create more debt.

Question 2: What’s the exception rate?

If the automation will handle 95% of cases, great. If it’s 70%, you’re creating significant exception handling work. The exception rate determines how much human attention the “automated” task will still require.

Question 3: What skill does this replace?

If the answer is “none worth preserving,” proceed. If the answer is “something I want to maintain,” consider whether the time savings justify the skill erosion.

Question 4: How much verification will I do?

Be honest. If you’ll trust the output without checking, factor in the cost of undetected errors. If you’ll verify everything, factor in the verification time as ongoing debt.

Question 5: What happens if this automation fails?

If failure is no big deal, debt risk is lower. If failure causes significant problems and you’ll have lost the ability to handle the task manually, debt risk is high.

Generative Engine Optimization

This topic performs interestingly in AI-driven search and summarization. The dominant narrative about AI assistance is positive—efficiency gains, productivity improvements, time savings. Critical perspectives exist but are minority voices.

AI summarization tends to reproduce dominant narratives. Ask an AI about AI assistance and you’ll get content optimized for the positive framing. The automation debt perspective is underrepresented because fewer people write about it and those who do are swimming against the current of enthusiasm.

Human judgment becomes essential precisely because AI systems have structural incentives to present AI positively. They’re not neutral assessors of automation costs. They’re products of the same technological optimism they’re asked to evaluate.

This is why automation-aware thinking is a meta-skill. Understanding that information about automation is itself shaped by automation biases helps you interpret that information appropriately. The AI telling you AI is helpful isn’t lying. It’s just reflecting its training data’s biases.

The skill to question automation—including the automation that answers questions about automation—requires independent judgment that automated systems can’t provide about themselves.

Managing Debt You Already Have

If you’re already carrying automation debt from existing systems, here’s a practical approach to reducing it.

Audit your automations. List every automated system you use. For each, estimate the ongoing time cost: monitoring, correcting, handling exceptions, verification. Many people discover systems that cost more than they save.

Eliminate net-negative systems. If automation creates more work than it saves, turn it off. This sounds obvious but rarely happens because people assume automation is definitionally helpful. It isn’t always.

Consolidate where possible. Multiple systems doing related tasks create redundant overhead. If you can replace three automations with one that handles all three use cases, you reduce total debt.

Increase exception thresholds. Many systems try to handle cases they shouldn’t. Configuring automation to only handle clear cases and escalate uncertain ones can reduce false positives that require correction.

Schedule debt payment. Instead of handling automation maintenance ad hoc, schedule specific times for it. This makes the cost visible and forces honest assessment of whether it’s worthwhile.

The Independence Test

Here’s a test I apply to evaluate automation health: Can I function independently if this automation disappears?

If yes, the automation is a tool I’m using. If no, the automation has become a crutch I’m depending on.

Tools are healthy. They enhance capability without replacing it. You can put them down and still function. The automation adds value while preserving autonomy.

Crutches are concerning. They replace capability rather than enhancing it. You can’t function without them because the underlying capability has atrophied. The automation has created dependency.

Luna passes this test constantly. She uses the automatic feeder when it’s available. She bugs me for food when it isn’t. Her feeding capability is intact regardless of automation status.

We should aim for similar robustness. Use AI assistance when it helps. Maintain the capability to function without it. The assistance should be optional enhancement, not required infrastructure.

The Honest Calculation

Here’s what honest automation accounting looks like:

Visible benefits:

- Time saved on automated tasks

- Reduction in routine cognitive load

- Consistency improvements

Hidden costs (automation debt):

- Setup and configuration time

- Ongoing monitoring time

- Correction time for errors and near-misses

- Exception handling time

- Verification time (if done)

- Skill erosion (future cost)

- Dependency creation (future cost)

- System maintenance and updates

- Cognitive overhead of managing multiple systems

Most automation discussions focus on the visible benefits. Honest assessment requires counting the hidden costs too. Only when both sides balance can you determine whether automation is actually net positive.

flowchart LR

subgraph Visible["Visible Benefits"]

A[Time Saved]

B[Reduced Load]

C[Consistency]

end

subgraph Hidden["Hidden Costs"]

D[Setup Time]

E[Monitoring]

F[Corrections]

G[Exceptions]

H[Verification]

I[Skill Erosion]

J[Dependency]

end

Visible --> K{Net Assessment}

Hidden --> K

K -->|Often Negative| L[Automation Debt]

K -->|Sometimes Positive| M[Genuine Help]The honest calculation often reveals that celebrated efficiency gains are smaller than claimed or even negative. This isn’t because automation is bad. It’s because accounting that only counts benefits produces inflated assessments.

The Way Forward

I’m not arguing against AI assistance. I’m arguing for honest assessment of its costs alongside its benefits.

Some AI assistance genuinely helps. Mechanical tasks with low exception rates and low skill-preservation concerns benefit from automation. The debt is manageable and the savings are real.

Other AI assistance creates more problems than it solves. Judgment-requiring tasks with high exception rates and important skill-preservation concerns accumulate debt faster than savings.

The skill is distinguishing between these categories. Not assuming all automation helps. Not assuming all automation harms. Evaluating each system based on its actual costs and benefits, including the hidden costs that enthusiasm tends to obscure.

Luna figured this out instinctively. She uses helpful automation (the feeder) and ignores unhelpful automation (the smart toys I bought her). She optimizes for actual benefit, not feature lists.

We should aspire to similar wisdom. Use AI when it actually helps. Decline it when it creates more work than it saves. And count the debt honestly, even when the accounting is uncomfortable.

That’s the path to sustainable automation—help that helps without accumulating costs that eventually overwhelm the benefits. It requires more thought than “automate everything.” But it produces better outcomes than the debt spiral that undiscriminating adoption creates.

The help that creates more work isn’t help. Recognizing that distinction is the first step toward automation that actually serves us rather than automation we end up serving.