Why Privacy Is the New Luxury of the Digital Era

The Price of Free

Nothing is free. This axiom is older than the internet, but the internet gave it new meaning. When you don’t pay for a product, you are the product. When you do pay for a product, you might still be the product. The economics of attention have made your data more valuable than your dollars.

My British lilac cat, Mochi, receives free treats from visitors. She considers this her due—compensation for the privilege of her presence. She’s not wrong about the transaction, just about who benefits most. The visitors get photos for social media. Mochi gets a treat. The platforms hosting those photos get data about visitor demographics, pet ownership patterns, and behavioral signals. Who really won?

Privacy was once the default state. You lived your life, and unless you were notable, no one tracked your movements, catalogued your preferences, or analyzed your relationships. That world ended. We now live in the inverse: surveillance is the default, privacy the exception.

The exception costs money. Privacy has become a luxury good—available to those who can afford the premium devices, the paid services, and the time to configure protective settings. Like organic food or clean air, privacy is now something you purchase rather than inherit.

This article examines privacy through the lens of three technology empires: Apple, Google, and Meta. Each has built a trillion-dollar business. Each takes a fundamentally different approach to user data. Understanding these approaches helps you make informed choices about which companies get access to your digital life.

Understanding the Privacy Economy

Before comparing the big three, we need to understand how the privacy economy works. Companies don’t harvest data for fun. They harvest data because it’s profitable. The question is: profitable for whom, and at what cost to users?

The Attention Model treats user attention as the primary product. Companies like Meta and Google’s advertising business monetize by capturing attention and selling access to it. The more they know about you, the more precisely they can target ads, the more they can charge advertisers. Your data is the raw material; your attention is the product.

The Hardware Model treats devices as the primary product. Companies like Apple monetize by selling hardware at premium margins. User data can enhance the product experience but isn’t required for revenue. Apple’s incentive is keeping customers satisfied enough to buy the next device.

The Hybrid Model combines elements of both. Google sells hardware (Pixel phones, Nest devices) while running the world’s largest advertising business. This creates tension: the hardware benefits from privacy protection, the advertising benefits from data collection.

These models create different privacy incentives:

| Model | Primary Revenue | Privacy Incentive |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Advertising | Collect more data |

| Hardware | Device sales | Protect user data |

| Hybrid | Both | Conflicted |

The model shapes the product. When you use a free service, consider which model applies. The answer tells you how your data will be treated.

Apple: Privacy as Product Positioning

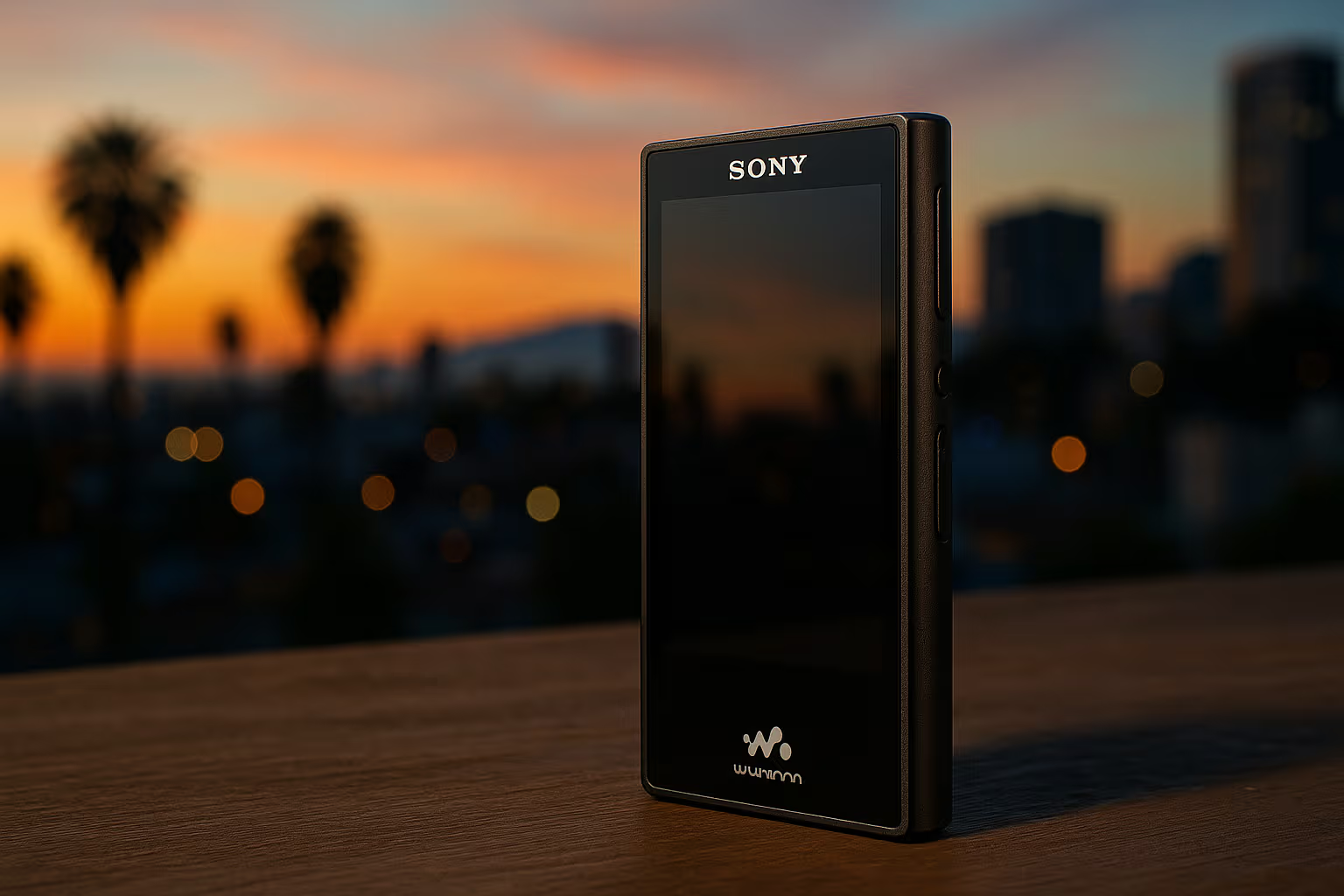

Apple has made privacy a core brand attribute. “What happens on your iPhone stays on your iPhone” proclaimed their billboards. Privacy features receive keynote stage time. Executives speak about privacy as a human right.

Is this genuine commitment or marketing positioning? The honest answer: it’s both. Apple genuinely implements strong privacy protections. Apple also benefits commercially from doing so.

The Business Case for Apple Privacy

Apple makes money selling hardware and services. Unlike Google and Meta, Apple doesn’t need your behavioral data to generate revenue. This alignment of business model and privacy protection is genuine and important.

Apple also differentiates from competitors. In a market where Android phones offer comparable hardware at lower prices, privacy becomes a justification for Apple’s premium. “Yes, this phone costs more, but it respects your privacy” is a coherent value proposition.

What Apple Actually Does

Apple’s privacy features are substantial:

-

App Tracking Transparency (ATT) requires apps to ask permission before tracking across other apps and websites. This single feature cost Meta an estimated $10 billion in advertising revenue.

-

Mail Privacy Protection hides your IP address and prevents senders from knowing when you open emails.

-

iCloud Private Relay encrypts web traffic and hides your IP address from websites (though not a full VPN).

-

On-Device Processing keeps sensitive data (face recognition, health data, Siri requests) on your device rather than sending it to Apple servers.

-

Privacy Labels in the App Store show what data apps collect before you download them.

-

Lockdown Mode provides extreme protection for high-risk users (journalists, activists, executives).

Apple’s Privacy Limitations

Apple’s privacy is not absolute:

-

Apple complies with government requests for data. In countries with aggressive surveillance laws, this compliance can be substantial.

-

iCloud data (unless Advanced Data Protection is enabled) is accessible to Apple and can be provided to authorities with legal requests.

-

Apple’s advertising business (smaller than Google’s but growing) does use some user data for targeting.

-

The App Store’s commission structure creates conflicts—Apple profits from apps that might compromise privacy.

-

China represents Apple’s largest manufacturing base and second-largest market. Apple makes compromises in China that it wouldn’t make in Western markets.

The Apple Privacy Grade: B+

Apple deserves credit for substantial privacy protections that cost them nothing (or benefit them commercially) and for some protections that genuinely sacrifice potential revenue. They lose points for compromises made for business reasons, particularly in China, and for a services business that increasingly resembles the attention economy they criticize.

Google: The Conflicted Giant

Google presents the most complex privacy case. The company runs the world’s most profitable advertising business, built entirely on user data. Yet Google also employs world-class security researchers, develops privacy-enhancing technologies, and genuinely protects users from third-party threats.

Google doesn’t want others to have your data. Google wants to be the only entity with your data. This creates a peculiar dynamic: excellent protection from external threats, complete exposure to Google itself.

The Data Google Collects

The scope is staggering:

- Search history: Every query you’ve ever made while logged in

- Location history: Everywhere you’ve been with an Android phone or Google app

- YouTube history: Every video watched, how long you watched, what you skipped

- Email content: Gmail scans email content (though no longer for advertising)

- Voice recordings: Assistant interactions, potentially ambient recordings

- Purchase history: Extracted from Gmail receipts

- Browsing history: If you use Chrome signed in

- App usage: From Android, what apps you use and how

- Contact information: Your entire social graph from contacts and communications

Google provides a dashboard (myactivity.google.com) where you can see much of this data. Viewing it is sobering. Google knows things about you that you’ve forgotten about yourself.

Google’s Privacy Efforts

Despite the data collection, Google does invest in privacy:

-

Privacy Sandbox aims to enable advertising without individual tracking, replacing cookies with cohort-based targeting.

-

Federated Learning allows machine learning on user data without that data leaving devices.

-

Differential Privacy adds noise to aggregated data to prevent identification of individuals.

-

Advanced Protection Program provides maximum security for high-risk users.

-

Security Team (Project Zero) finds and reports vulnerabilities in all software, not just Google’s.

These efforts are genuine but serve Google’s interests. Privacy Sandbox eliminates third-party cookies—which helps user privacy but also cements Google’s advertising advantage by eliminating competitors’ data access.

The Android Paradox

Android is open source. Anyone can inspect the code. Yet Android phones, as shipped by manufacturers, often include extensive tracking by Google, the manufacturer, and the carrier. The openness enables privacy-focused variants (GrapheneOS, CalyxOS) but doesn’t guarantee privacy in practice.

Google’s data collection on Android is extensive but can be limited. You can disable location history, pause activity tracking, and use privacy-focused settings. But these options are buried in menus, off by default, and sometimes confusingly labeled. The default experience prioritizes data collection.

The Google Privacy Grade: C

Google provides excellent security against external threats. Google provides minimal protection against Google itself. The company’s core business requires your data, and despite genuine privacy engineering, the fundamental model conflicts with user privacy.

Meta: The Surveillance Business Model

Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Threads) operates the purest attention economy business. The company’s entire revenue comes from advertising. That advertising depends on targeting. That targeting depends on knowing everything possible about users.

Mark Zuckerberg once described Facebook’s approach: “The days of you having a different image for your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly.” This wasn’t presented as a bug—it was the product vision.

Meta’s Data Empire

Meta collects extensively:

- Social graph: Everyone you know, how you know them, how you interact

- Behavioral signals: What you click, what you linger on, what you skip

- Emotional reactions: Which content makes you angry, happy, sad, engaged

- Location data: Where you are, where you go, who you’re near

- Cross-site tracking: Meta’s pixel and SDK track you across much of the web

- Off-Facebook activity: Data purchased from brokers and shared by partners

The depth of inference is remarkable. Meta can predict life events (pregnancy, job change, relationship status) before you announce them. Meta knows your political views, your susceptibility to various appeals, your likely responses to different content.

WhatsApp: The Privacy Exception?

Meta acquired WhatsApp in 2014, and WhatsApp retains end-to-end encryption. Meta cannot read your WhatsApp messages. This is genuine privacy protection—but it’s not the whole story.

While message content is encrypted, metadata is not. Meta knows who you talk to, when, how often, and from where. Metadata alone reveals enormous amounts about relationships and behavior. And the WhatsApp app shares data with Meta for purposes other than message content.

Meta’s Privacy Record

Meta’s privacy history includes:

- Cambridge Analytica scandal (data misuse by third parties)

- FTC consent decree and $5 billion fine for privacy violations

- Repeated changes to privacy policies that expanded data sharing

- Ireland data protection authority fines exceeding €1 billion

- Secret research on teenage mental health that was not disclosed

The pattern isn’t occasional mistakes—it’s a business model that inherently conflicts with privacy.

Meta’s Privacy Improvements

Credit where due: Meta has implemented some privacy features:

- Privacy checkup tools to review settings

- Off-Facebook activity controls (though complex to use)

- End-to-end encryption for Messenger (finally enabled by default in 2024)

- Face recognition disabled by default (after years of default-on operation)

These improvements often came after regulatory pressure or public relations crises rather than proactive protection.

The Meta Privacy Grade: D

Meta’s business model is surveillance capitalism in its purest form. Privacy protections exist but are minimal, grudging, and frequently circumvented. Using Meta products means accepting extensive data collection as the cost of access.

flowchart TD

A[Your Data] --> B{Who Gets It?}

B --> C[Apple]

C --> C1[Minimal Collection]

C1 --> C2[On-Device Processing]

C2 --> C3[Premium Hardware Model]

B --> D[Google]

D --> D1[Extensive Collection]

D1 --> D2[Protected from Others]

D2 --> D3[Advertising Model]

B --> E[Meta]

E --> E1[Maximum Collection]

E1 --> E2[Shared with Partners]

E2 --> E3[Pure Advertising Model]Method

This comparative analysis draws from multiple sources:

Step 1: Policy Analysis I reviewed the privacy policies, terms of service, and data practices documentation from Apple, Google, and Meta. These documents reveal what companies can do with your data, not just what they say they do.

Step 2: Technical Review I examined technical documentation, security whitepapers, and third-party audits where available. This reveals actual implementation, not just policy claims.

Step 3: Regulatory Record I reviewed enforcement actions, fines, and consent decrees from regulators including the FTC, European data protection authorities, and state attorneys general. Regulatory actions reveal verified violations.

Step 4: Data Access Testing I downloaded my data from each company using their data export tools (Google Takeout, Facebook Download Your Information, Apple Privacy). Reviewing what each company actually has is informative.

Step 5: Expert Consultation I consulted privacy researchers, security professionals, and policy experts who study these companies professionally.

The Real Cost of Free

When Meta offers free social networking and Google offers free email, search, and maps, the cost appears to be zero. The actual cost is your privacy—and that cost is difficult to quantify.

Economic costs: Your data enables targeting that influences purchases, potentially costing you money on products you wouldn’t have bought otherwise.

Manipulation costs: Precisely targeted content can influence opinions, votes, and behaviors. The 2016 election interference demonstrated how personal data enables manipulation at scale.

Discrimination costs: Data-driven decisions in employment, credit, insurance, and housing can discriminate. You may never know why you didn’t get the job, the loan, or the apartment.

Security costs: Aggregated data is a hacking target. Breaches expose everything collected—not just what you thought you were sharing.

Future costs: Data collected today might be used in ways we can’t anticipate. The permanence of digital records means youthful indiscretions persist indefinitely.

These costs are real but dispersed and difficult to attribute. You don’t know which manipulation worked, which opportunity you lost, or which future harm awaits. The asymmetry of information—companies know what your data reveals, you don’t—prevents informed consent.

Practical Privacy Protection

Given the landscape, what can you actually do? Perfect privacy is impossible without complete disconnection. Practical privacy requires tradeoffs. Here’s a realistic approach:

Tier 1: Basic Hygiene (Everyone Should Do This)

- Review permissions: Audit which apps have access to location, microphone, camera, contacts. Remove unnecessary permissions.

- Use different email addresses: Separate email for important accounts from email for newsletters and marketing.

- Enable two-factor authentication: Everywhere that offers it, using an authenticator app rather than SMS.

- Update regularly: Security updates patch vulnerabilities that compromise privacy.

- Check privacy settings: Spend 30 minutes reviewing privacy settings on major platforms.

Tier 2: Moderate Protection (Privacy-Conscious Users)

- Switch browsers: Use Firefox or Brave instead of Chrome. Enable tracking protection.

- Use a password manager: Unique passwords for every site reduce cross-site exposure from breaches.

- Limit social media: Reduce what you share, who can see it, and how much time you spend.

- Audit data access: Download your data from Google, Facebook, etc. to see what they have.

- Consider paid alternatives: Email providers like ProtonMail or Fastmail; search engines like Kagi.

Tier 3: Serious Protection (High-Risk Individuals)

- Use Signal: For messaging with actual security.

- Use a VPN: From a reputable provider, for browsing privacy.

- Consider GrapheneOS: Privacy-focused Android fork, if you’re technical.

- Separate devices: Different devices for different purposes.

- Hardware keys: For two-factor authentication on critical accounts.

Tier 4: Maximum Protection (Journalists, Activists, Targets)

- Enable Lockdown Mode: On Apple devices.

- Air-gapped devices: For truly sensitive work.

- Operational security training: From organizations like EFF or Freedom of the Press Foundation.

- Legal preparation: Understanding your rights in your jurisdiction.

Most people need Tier 1 and some of Tier 2. Tier 3 and 4 are for specific threat models that most users don’t face.

Generative Engine Optimization

The relationship between privacy and Generative Engine Optimization is significant. AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini are trained on massive datasets that include content people created without expecting it to be machine learning training data.

The privacy implications are layered:

Training data privacy: Content you posted publicly might train AI models. The assumption of obscurity—that public content is effectively private because no one would find it—no longer holds when AI can process everything.

Inference privacy: AI can infer sensitive information from seemingly innocuous data. Writing style, vocabulary, topic interests, and behavioral patterns can reveal identity, location, profession, and personal details.

Interaction privacy: Conversations with AI assistants may be logged, reviewed, and used for training. OpenAI and Anthropic have different policies here, but the concern exists.

For practitioners, this means:

- Consider what you share with AI systems, particularly in business contexts

- Review privacy policies of AI providers you use

- Understand that prompts and outputs may be retained

- Use business-tier offerings with stronger privacy commitments for sensitive work

The GEO skill of prompt engineering has a privacy dimension. Craft prompts that achieve your goals without revealing more than necessary. Use the capabilities while protecting yourself.

The Luxury Goods Analogy

Privacy has become a luxury good in several ways:

Price premium: Apple devices cost more than Android alternatives. Paid email costs more than free email. Privacy-respecting services often charge more than ad-supported alternatives.

Knowledge premium: Understanding privacy settings, alternatives, and best practices requires time and expertise that not everyone has.

Convenience premium: Privacy-protecting alternatives often require more effort—more steps, more configuration, more friction.

Social premium: Network effects make privacy choices socially costly. Not being on Facebook or Instagram means missing social connections.

Like other luxury goods, privacy marks social position. The wealthy can afford Apple devices, paid services, and the time to configure them. The knowledge workers understand the tradeoffs and make informed choices. Everyone else gets the free products with the hidden costs.

This is troubling. Privacy shouldn’t be a luxury. It should be a right. But until regulation changes the economics, the market outcome is privacy for those who can afford it.

The Regulatory Landscape

Regulation is attempting to level the playing field:

GDPR (Europe) provides rights to access, correct, and delete data, plus requirements for consent and data protection by design. Fines for violations can reach 4% of global revenue.

CCPA/CPRA (California) provides similar rights with some differences, setting a partial standard for the US.

DMA/DSA (Europe) targets specifically the large platforms, requiring interoperability and limiting some anti-competitive practices.

Proposed federal legislation (US) would create national privacy standards, though passage remains uncertain.

Regulation matters because it changes the economics. When violating privacy becomes expensive, companies invest in protection. Meta’s billion-euro fines changed behavior where user preferences didn’t.

Future Trajectories

Where is privacy heading? Several trends are visible:

Increased regulation: More jurisdictions are passing privacy laws. The direction is toward more protection, not less.

Privacy as competitive advantage: As users become more aware, privacy becomes a differentiator. Apple has shown this works commercially.

Privacy-enhancing technologies: Techniques like differential privacy, federated learning, and homomorphic encryption enable functionality without exposure.

Decentralized alternatives: Blockchain-based identity, decentralized social networks, and self-sovereign data models offer alternatives to centralized surveillance.

AI-driven surveillance: On the other side, AI enables more sophisticated surveillance, inference, and manipulation. The arms race continues.

The outcome isn’t determined. User awareness, regulatory action, and competitive pressure all influence whether privacy becomes more accessible or more stratified.

Making Your Choice

Given all this, what should you do? The answer depends on your threat model and your values.

If you primarily want convenience and don’t feel personally targeted, Google’s ecosystem offers excellent functionality with surveillance as the cost. You can mitigate some exposure through settings.

If you value privacy and can afford the premium, Apple’s ecosystem offers meaningful protection with some limitations. The additional cost buys real privacy benefits.

If you need maximum privacy, specialized tools and practices exist but require effort and sacrifice some convenience. This is appropriate for specific threat models, not for everyone.

For most people, the practical approach is:

- Understand the tradeoffs of platforms you use

- Implement basic privacy hygiene (Tier 1)

- Consider paid alternatives for your most sensitive activities

- Support privacy regulation that makes protection universal rather than luxury

Mochi doesn’t worry about privacy. Her life is local—she exists in physical space, leaving no digital trail beyond the photos visitors take. Perhaps there’s wisdom there. The most private life is the least connected one. But for those of us living in the digital world, the question isn’t whether to engage but how to engage with awareness.

Privacy is the new luxury because the default has changed. Surveillance is free; privacy costs extra. But knowing the cost is the first step to deciding what you’re willing to pay—in money, convenience, or exposure.

Choose deliberately. What you share, who you share it with, and what they can do with it matters more than ever. The digital era has made privacy precious precisely because it’s no longer guaranteed. Treat it accordingly.