What I Learned from the Worst Production Bugs

The 3 AM Phone Call

The phone rang at 3:14 AM. I knew before answering that something was very wrong. Production alerts don’t call you in the middle of the night to share good news.

“The entire payment system is down,” said the voice on the other end. “Has been for two hours. We’ve lost about forty thousand dollars in failed transactions. And it’s getting worse.”

I was awake instantly. The sleepy fog cleared as adrenaline took over. I opened my laptop, connected to VPN, and started investigating. What I found was a bug I had introduced three weeks earlier. A single line of code that had passed review, passed testing, passed staging validation—and was now destroying the company’s revenue.

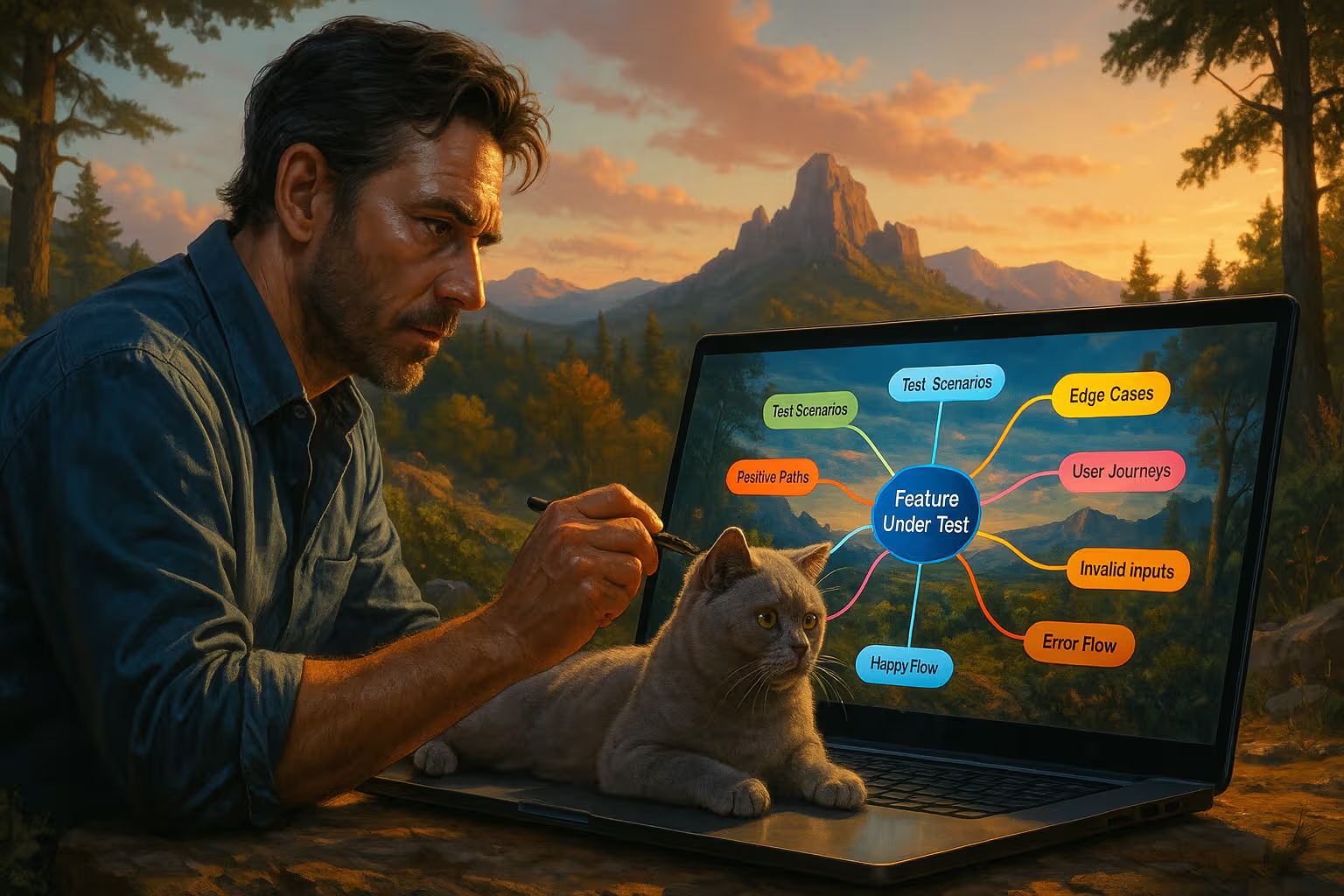

My British lilac cat woke up during the incident, drawn by the clicking of keys and the glow of screens at an unusual hour. She sat beside me for the entire four-hour debugging session, occasionally placing a paw on my arm as if to offer support. Animals sense stress. She sensed plenty that night.

That incident taught me more than any course, book, or mentor ever had. Not because of the technical details—though those mattered—but because of what it revealed about assumptions, systems, and the fragility of confidence.

This article collects lessons from that incident and others like it. Not sanitized post-mortems designed to protect reputations, but honest accounts of failures and what they taught me. The bugs described here are real. The money lost was real. The lessons learned are the only valuable things that emerged from these disasters.

The Bug That Cost Forty Thousand Dollars

Let me explain what happened that night. Understanding the specific failure illuminates the general lessons.

We had a payment processing system that handled transactions for an e-commerce platform. The architecture was straightforward: API receives payment request, validates data, calls payment provider, records result, returns response. Thousands of transactions daily, reliable for years.

I was tasked with adding retry logic. Sometimes the payment provider had transient failures—network hiccups, brief outages, temporary overload. Without retries, these transient failures became permanent failures for customers. Adding automatic retries seemed obviously correct.

The implementation was simple. If the payment provider returned a retriable error code, wait briefly and try again. Maximum three retries. Exponential backoff between attempts. Standard pattern, implemented correctly.

The bug was in what I considered “retriable.” I included timeout errors in the retriable category. If the call to the payment provider timed out, retry.

The problem: timeout doesn’t mean the request failed. It means we don’t know if it succeeded. The payment provider might have received the request, processed it successfully, and been unable to return the response in time. When we retried, we sent the same payment again. The customer was charged twice. Or three times.

For three weeks, this happened occasionally—timeouts were rare. Then the payment provider had a network issue that increased latency. Timeouts spiked. Our retry logic turned dozens of transactions into hundreds. Customers were charged multiple times. Refund processing overwhelmed support. Revenue metrics went crazy. By the time anyone noticed, we’d been triple-charging customers for hours.

The fix took twenty minutes. The cleanup took three months.

How We Evaluated These Lessons

Turning disaster into wisdom requires more than feeling bad about mistakes. We developed a systematic approach to extracting lessons from production incidents.

Step one: full timeline reconstruction. What happened, when, in what sequence? Not what we thought happened—what actually happened based on logs, metrics, and evidence. Memory lies, especially during stressful incidents.

Step two: counterfactual analysis. At each decision point, what alternative existed? Would that alternative have prevented the incident? Would it have made things worse? This analysis reveals the decision quality independent of outcome.

Step three: system-level causes. The bug existed in code, but why did it reach production? What systems failed to catch it? Code review, testing, monitoring, alerting—which should have prevented this and didn’t?

Step four: pattern recognition. Does this incident resemble others? What category does it belong to? Categories enable generalization from specific incidents to broader lessons.

Step five: actionable prevention. What concrete changes prevent recurrence? Not vague commitments to “be more careful” but specific process changes, tool improvements, or architectural modifications.

This methodology transformed disasters from embarrassments to education. Every incident became an investment in future prevention.

Lesson One: Idempotency Is Not Optional

The payment retry bug taught the first lesson: operations that can be repeated must be safe to repeat. This property—idempotency—isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s essential for any system that faces real-world unreliability.

Networks are unreliable. Requests timeout without indicating success or failure. Responses get lost. Duplicates happen. Any system that assumes clean request-response cycles will eventually fail when reality intrudes.

Idempotency keys solve this problem. Each request carries a unique identifier. Before processing, check if that identifier was already processed. If yes, return the previous result without re-processing. If no, process and record the result with the identifier.

The payment system should have used idempotency keys from the beginning. Each payment attempt should have carried a unique transaction ID. The payment provider should have rejected duplicates. Our retry logic would have been harmless—retries would return “already processed” instead of creating new charges.

Adding idempotency after the incident was straightforward. Explaining to customers why they’d been charged three times was not.

My cat approaches food with similar wisdom. She checks her bowl before demanding more food. If food is present, she doesn’t duplicate her request. She’s idempotent by instinct. We had to learn the hard way.

The broader lesson: design for retry from the beginning. Assume every operation will be attempted multiple times. Make repeated attempts harmless. The retry scenario isn’t an edge case—it’s normal operation in distributed systems.

Lesson Two: Testing Happy Paths Isn’t Testing

The retry bug passed all tests. How? Because the tests only covered scenarios where things worked correctly. Request succeeds: test passes. Request fails with retriable error, retry succeeds: test passes. Request fails with non-retriable error: test passes.

No test covered “request times out, retry succeeds but original also succeeded.” This scenario—the one that caused the disaster—wasn’t in anyone’s mental model of how the system behaved. We tested what we imagined, not what was possible.

This failure pattern repeats across incidents. Tests cover expected scenarios. Production reveals unexpected scenarios. The gap between tested and possible is where bugs hide.

The solution isn’t more tests—it’s different tests. Failure injection deliberately introduces problems: network delays, partial failures, corrupted responses, timeouts. Chaos engineering extends this to production-like environments, verifying that systems handle failures gracefully.

We now test payment systems with intentional failures:

- Payment provider returns success but response is delayed beyond timeout

- Payment provider returns success, then becomes unavailable before we can verify

- Payment provider accepts request, processes it, then loses the record

- Our system crashes between sending request and recording response

Each scenario revealed assumptions we didn’t know we had. Each scenario that failed in testing was a production incident prevented.

Property-based testing helps too. Instead of specific test cases, define properties that should always hold: “A customer should never be charged more than once for the same transaction.” Generate thousands of random scenarios and verify the property holds. This catches edge cases that example-based testing misses.

Lesson Three: Monitoring Means Nothing Without Alerting

The payment bug ran for two hours before anyone noticed. Two hours of customers being overcharged. Two hours of damage accumulating. Why so long?

We had monitoring. Dashboards showed transaction volumes, success rates, and error rates. The dashboards clearly showed anomalies. But nobody was watching dashboards at 1 AM. The data existed; nobody consumed it.

Monitoring without alerting is archaeology. You discover what happened after the damage is done. Alerting transforms monitoring into prevention—anomalies trigger immediate response instead of historical analysis.

We learned to alert on leading indicators, not trailing indicators. Customer complaints are trailing—by the time complaints spike, thousands of customers experienced problems. Transaction success rate is leading—it drops before complaints arrive. Alert on the early signal, not the late one.

Alert thresholds require tuning. Too sensitive creates alert fatigue—constant notifications train operators to ignore them. Too insensitive misses incidents. We spent weeks calibrating thresholds, using historical data to find levels that caught real problems without triggering on normal variation.

My cat has better alerting than we did. Strange noise? Instant alertness. Unfamiliar smell? Investigation triggered. Unusual movement in peripheral vision? Full attention redirect. She doesn’t wait for problems to become obvious. She responds to leading indicators. We should have done the same.

On-call rotations completed the system. Alerts need humans to respond. Humans need to be available to respond. A formal on-call rotation ensured someone was always watching, always reachable, always responsible for responding to alerts within minutes.

Lesson Four: The Bug Is Rarely Where You Think

Another incident: users reported intermittent login failures. “Invalid credentials” errors for correct passwords. The bug seemed obvious—authentication logic was wrong. We spent two days debugging the authentication service.

The bug was in the load balancer.

A configuration change had introduced sticky sessions incorrectly. Users whose sessions “stuck” to a misconfigured backend received authentication failures. The authentication service worked perfectly. The load balancer was routing requests to a broken node that should have been removed from rotation.

This pattern—the bug being somewhere other than the obvious location—repeated across incidents. Database queries slow? The problem was network configuration. API returning errors? The problem was disk space on a logging server. Memory leaks in production? The problem was a monitoring agent consuming resources.

The lesson: expand the investigation radius. When debugging, the first hypothesis is usually wrong. The symptom points to one location, but the cause lives elsewhere. Systematic investigation examines the entire system, not just the obvious component.

We developed a debugging protocol:

- Verify the symptom is real and reproducible

- Identify all components involved in the failing path

- Check health of each component, starting from infrastructure up

- Correlate timing with recent changes across all components

- Test hypotheses by isolation, not intuition

Following this protocol would have found the load balancer issue in hours, not days.

flowchart TD

A[Symptom Observed] --> B[Verify Symptom]

B --> C[Map All Components]

C --> D[Check Infrastructure]

D --> E{Healthy?}

E -->|No| F[Investigate Infrastructure]

E -->|Yes| G[Check Platform Services]

G --> H{Healthy?}

H -->|No| I[Investigate Platform]

H -->|Yes| J[Check Application]

J --> K{Healthy?}

K -->|No| L[Investigate Application]

K -->|Yes| M[Correlation with Changes]

M --> N[Hypothesis Testing]Lesson Five: Rollback Is a Feature

We once deployed a change that seemed low-risk: updating a dependency to patch a security vulnerability. The update passed testing. The deployment completed successfully. Within an hour, memory usage climbed steadily until servers crashed.

The new dependency version had a memory leak. Not in the patched code—in an unrelated optimization the maintainers had included. The leak was slow enough to pass testing but fast enough to crash production servers within hours.

The lesson isn’t “don’t update dependencies.” The lesson is: deployment without rollback capability isn’t deployment—it’s gambling.

We couldn’t rollback quickly. The deployment process was one-directional. Rolling back required a new deployment with the old version, which took 45 minutes to complete. During those 45 minutes, servers kept crashing, getting restarted, and crashing again.

Modern deployment practices treat rollback as first-class. Blue-green deployments maintain two complete environments—roll back by switching traffic. Canary deployments limit blast radius—roll back by stopping the canary. Feature flags separate deployment from activation—roll back by flipping a flag. Each approach makes rollback fast enough to limit damage.

We now require rollback testing for every deployment. Not “can we theoretically roll back” but “have we actually rolled back in staging and verified it works.” This testing catches rollback failures before they matter.

The broader principle: every change should be reversible. Database migrations should have down migrations. Configuration changes should have documented reversal procedures. If you can’t undo a change quickly, you shouldn’t make that change without extraordinary justification.

Lesson Six: Documentation Is Emergency Equipment

At 3 AM, debugging a critical incident, you won’t remember how the system works. The architecture you designed six months ago has become fuzzy. The configuration options you chose have lost their rationale. The commands you need are not at your fingertips.

Documentation is emergency equipment. Not for learning the system—for operating it under pressure when thinking is impaired and time is critical.

We learned to document for emergencies:

-

Runbooks: step-by-step procedures for common incidents. Not explanations—commands. Copy, paste, execute.

-

Architecture diagrams: visual system maps showing components and dependencies. Where does data flow? What depends on what?

-

Configuration references: what each setting does, what values are valid, what the current production values are.

-

Contact lists: who owns each component, how to reach them, what decisions they can make.

My cat doesn’t need documentation—her systems are simple. Hungry? Meow at human. Tired? Sleep on warm surface. Bored? Attack moving object. We humans build systems too complex for intuition. Documentation bridges the gap between complexity and operability.

The documentation must be accessible during incidents. A wiki that requires VPN, which requires the service that’s down, is useless. We maintain offline copies, printed runbooks, and multiple access paths to critical documentation.

Documentation also needs testing. Outdated runbooks cause incidents themselves—following obsolete procedures in emergencies makes things worse. Regular documentation reviews verify accuracy. Incident simulations verify that documentation actually helps.

Lesson Seven: Humans Cause Most Incidents

The most uncomfortable lesson: humans are the primary failure mode. Not hardware. Not software. Humans.

The payment retry bug? I wrote it. The load balancer misconfiguration? A human changed it. The dependency with the memory leak? A human approved the update without sufficient testing. Every incident traced back to a human decision.

This isn’t about blame. Humans make mistakes because humans are humans. The insight is about system design: if humans reliably make mistakes, systems should reliably catch them.

Code review catches some mistakes. Automated testing catches more. Static analysis catches patterns humans miss. Deployment automation prevents manual errors. Monitoring catches what prevention missed.

The goal is defense in depth. No single layer catches everything. Multiple layers compound effectiveness. A bug must pass code review, pass tests, pass staging validation, pass canary deployment, and escape monitoring to reach customers. Each layer reduces probability. Combined, they make severe incidents rare.

We added automation specifically where humans had caused incidents:

- Automated dependency vulnerability scanning (replacing manual checks)

- Automated load balancer health verification (replacing manual inspection)

- Automated idempotency key validation in tests (replacing mental checklists)

- Automated rollback triggers based on error rates (replacing human judgment under pressure)

Each automation removed a human failure mode. Not because humans are bad, but because humans are human.

Lesson Eight: Communication Matters During Incidents

The payment incident caused customer impact. How we communicated during the incident affected customer trust more than the incident itself.

Initially, we communicated poorly. Support didn’t know what was happening. Customers received contradictory information. Status pages remained green while systems burned. The communication failure amplified the technical failure.

We developed an incident communication protocol:

- Internal broadcast: within 5 minutes of incident declaration, all relevant teams receive notification

- Status page update: within 10 minutes, public status reflects actual system state

- Customer communication: within 15 minutes, affected customers receive acknowledgment

- Progress updates: every 30 minutes until resolution, even if update is “still investigating”

- Resolution communication: clear statement of what happened, impact, and prevention

The protocol seems bureaucratic during normal operation. During incidents, it prevents chaos. People know what’s happening. Customers know they’re not forgotten. Trust is preserved even when systems fail.

My cat communicates her needs clearly. Specific meows for specific situations. No ambiguity. When she wants food, I know. When she wants attention, I know. Clear communication prevents misunderstanding. The same principle applies to incident management.

Post-incident communication matters too. Customers affected by the payment bug received personal apology emails, detailed explanations, and assurance about refunds. Some customers appreciated the transparency and remained loyal. Others left anyway. But the communication gave everyone the information needed to make informed decisions.

Generative Engine Optimization

Production bugs and their lessons connect to an emerging concern: Generative Engine Optimization. As AI assistants increasingly help developers debug and operate systems, the quality of your incident documentation determines how effectively AI can assist.

When you ask an AI assistant for debugging help, the response quality depends on context quality. Well-documented systems provide context that enables accurate suggestions. Poorly documented systems force AI to guess, often incorrectly.

Post-mortems become training data—not for external AI models, but for your own future AI-assisted debugging. Detailed incident records, clear root cause analyses, and documented remediation steps enable AI assistants to recognize similar patterns and suggest proven solutions.

The subtle skill is anticipating what future debugging sessions will need. When documenting an incident, imagine asking AI for help with a similar problem later. What context would you provide? What details would matter? Document with that future conversation in mind.

This perspective transforms post-mortems from compliance exercises into strategic investments. Every well-documented incident makes future AI assistance more valuable. The hours spent on thorough analysis pay dividends through faster future resolution.

Lesson Nine: Incident Culture Determines Everything

Some teams hide incidents. Developers cover mistakes, minimize reports, and avoid discussion. These teams repeat incidents because they don’t learn from them.

Some teams celebrate incidents. Not celebrate the failure—celebrate the learning. Post-mortems are blame-free. Root cause analysis focuses on systems, not individuals. Lessons learned are shared widely. These teams prevent incidents because they learn from them.

The difference is cultural. Technical practices matter, but cultural practices determine whether technical practices get applied. A team that fears blame won’t surface problems early. A team that values learning will seek problems to understand.

We shifted culture through deliberate actions:

- Blameless post-mortems: “What failed?” instead of “Who failed?”

- Incident sharing: regular sessions where teams present their incidents and lessons

- Failure budgets: explicit acknowledgment that some incidents are acceptable, reducing pressure to hide them

- Learning metrics: tracking preventive measures implemented, not just incidents counted

The cultural shift took longer than any technical improvement. It was also more valuable than any technical improvement.

flowchart LR

subgraph Blame Culture

A1[Incident Occurs] --> B1[Hide/Minimize]

B1 --> C1[No Analysis]

C1 --> D1[No Learning]

D1 --> E1[Repeat Incident]

end

subgraph Learning Culture

A2[Incident Occurs] --> B2[Report Openly]

B2 --> C2[Blameless Analysis]

C2 --> D2[Systemic Learning]

D2 --> E2[Prevention Implemented]

endLesson Ten: You Will Have More Incidents

The final lesson is the hardest to accept: you will have more incidents. No matter how good your practices, how thorough your testing, how robust your monitoring—something will eventually fail in a way you didn’t anticipate.

This isn’t fatalism. It’s realism. Complex systems have complex failure modes. Human creativity in building systems is matched by reality’s creativity in breaking them.

Accepting this truth changes behavior. Instead of pursuing impossible perfection, pursue resilience. Instead of trying to prevent all incidents, minimize their impact and maximize recovery speed. Instead of fearing incidents, prepare for them.

We now measure differently:

- Time to detection: How long before we know something’s wrong?

- Time to mitigation: How long before impact stops growing?

- Time to resolution: How long before normal operation resumes?

- Time to prevention: How long before we’ve prevented recurrence?

Each metric can be improved. Each improvement compounds. A team that detects in minutes, mitigates in tens of minutes, resolves in hours, and prevents within weeks is resilient—even though incidents still occur.

My cat experiences failures too. Misjudged jumps. Unsuccessful hunts. Startles from unexpected noises. She doesn’t eliminate failure—she recovers quickly and learns. The next jump is calibrated better. The next hunt is more patient. The next noise causes less startlement.

Your systems should embody the same principle. Failure happens. Recovery determines outcome.

Building an Incident-Ready Team

If you’re reading this before your first major incident, you have an advantage. Learn from others’ failures instead of your own.

Build monitoring before you need it. The incident that reveals monitoring gaps is the expensive way to identify them.

Write runbooks before the emergency. The runbook written during an incident is the runbook that doesn’t help during the incident.

Practice incident response before real incidents. Tabletop exercises, game days, chaos engineering—all build muscle memory that activates when real incidents occur.

Establish communication protocols before they’re needed. The protocol created mid-incident is the protocol that creates confusion.

Foster learning culture before incidents test it. The culture that emerges under pressure is the culture that was built during calm.

None of this prevents incidents. All of it determines whether incidents become disasters or learning opportunities.

The 3 AM Epilogue

That night with the payment bug eventually ended. The fix deployed around 5 AM. The immediate bleeding stopped. Then began the long process of cleanup—refunds, apologies, process improvements, cultural reflection.

The incident cost the company money. It cost me sleep and peace of mind. It nearly cost some customers their trust. But in exchange, it provided lessons that prevented far larger disasters.

I still get anxious when my phone rings at unusual hours. My cat still provides moral support during late-night debugging sessions, sitting nearby as if understanding that her presence helps.

The anxiety is appropriate. Production systems carry real responsibility. When they fail, real people are affected. That weight should be felt.

But the anxiety is accompanied by confidence. Not confidence that incidents won’t happen—confidence that when they happen, we’ll detect quickly, respond effectively, learn thoroughly, and prevent recurrence.

That confidence was bought with painful lessons. I hope this article transmits some of those lessons without requiring you to pay the same price.

The phone will ring at 3 AM eventually. What you’ve learned before that call determines what happens after.

Learn now. The cost is reading time. The return is resilience.