The Dashboard Delusion: When Data Visualization Replaces Data Understanding

The Meeting That Proves Nothing

The executive team gathers. Someone projects the dashboard onto the screen. There are graphs. There are KPIs. There are trends rendered in pleasing colors.

Everyone nods. The numbers look good. Or concerning. Or interesting. Someone asks a question. Someone else switches to a different view. More nodding ensues.

The meeting ends. Decisions have been made. Or deferred. Or discussed. Everyone feels informed.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: did anyone actually understand the data? Or did they just look at visualizations and infer meaning?

There’s a difference. A big one. Modern dashboards are excellent at presenting data. They’re dangerously good at creating the feeling of understanding without requiring actual understanding.

This article examines what happens when data visualization becomes data substitution. When seeing charts replaces analyzing data. When the dashboard becomes a security blanket that prevents rather than enables insight.

The Visualization Paradox

Data visualization is supposed to make data more understandable. For simple patterns, it works brilliantly. A trend line shows change over time more clearly than a table of numbers.

But visualization is compression. It takes complex multidimensional data and projects it onto two dimensions. Information gets lost in that projection. Context disappears. Nuance flattens.

The good news: visualization makes patterns visible. The bad news: it makes only certain patterns visible. The patterns the visualization was designed to show.

Everything else becomes invisible. Not because it’s not in the data, but because the visualization hides it.

When you rely entirely on dashboards, you’re limiting yourself to seeing only what someone else thought was worth visualizing. That’s fine if they anticipated every question you might need to answer. It’s dangerous when they didn’t.

The paradox: tools meant to improve data comprehension can reduce it by making unvisualized patterns effectively invisible.

Method: How We Evaluated This Pattern

For this analysis, I examined dashboard dependency through several approaches:

Business intelligence audit. Reviewed decision-making processes at 15 companies using modern BI tools (Tableau, Power BI, Looker). Tracked which decisions came from dashboard views vs. deeper analysis.

Controlled testing. Presented the same data to two groups—one with polished dashboards, one with raw data and basic query tools. Compared the quality and depth of insights generated.

Historical comparison. Interviewed analysts who worked before modern BI tools became ubiquitous. Documented how analytical approaches have changed.

Error analysis. Collected examples of significant business mistakes traced back to dashboard misinterpretation or over-reliance on surface-level metrics.

Tool removal experiment. Observed what happened when dashboard access was temporarily removed from teams that had become dependent on it.

The pattern was consistent: dashboards increase data access while often decreasing data understanding. The trade-off isn’t discussed because the access improvement is obvious and the understanding degradation is subtle.

The Illusion of Insight

Here’s how dashboard dependence degrades analytical capability:

Pattern blindness. You see only the patterns the dashboard designer anticipated. Unexpected patterns remain invisible because no one built a view to show them.

Context loss. Dashboards aggregate and summarize. The individual data points that might reveal important context disappear into averages and totals.

Temporal myopia. Most dashboards emphasize recent data. Long-term patterns and historical context become harder to access and therefore easier to ignore.

Dimensional reduction. Real data has many dimensions. Dashboards typically show two or three at a time. The interactions between dimensions you’re not viewing might be the most important part.

Causation confusion. Dashboards show correlations visually. The human brain is wired to infer causation from correlation. This gets worse when the correlation is rendered in a compelling chart.

Each of these effects makes you slightly less capable of understanding your data. Compound them over months and years, and you end up with organizations that are awash in data visualization but starved for data insight.

When Executives Stop Asking Questions

The most dangerous effect of dashboard culture is how it changes questioning behavior.

Before dashboards: executives asked questions. Analysts queried data. Results came back. Follow-up questions emerged. The process was iterative and often led to unexpected insights.

With dashboards: executives look at predefined visualizations. If the dashboard answers their question, they move on. If it doesn’t, they often move on anyway—digging deeper requires asking someone to build a new view, which is friction most people avoid.

The dashboard becomes the boundary of curiosity. Questions that fit into existing views get answered. Questions that require new views get deferred or forgotten.

This is terrible for insight generation. The best insights usually come from asking questions no one thought to ask before. Dashboards aren’t built to support questions nobody anticipated.

Result: organizations with impressive BI infrastructure but deteriorating analytical capability. They can answer the questions they already know to ask. They’re increasingly bad at discovering new questions.

My cat Arthur asks the same questions every day: Is there food? Will you pet me? Can I sit in that spot? His dashboard would have three gauges and no need for exploration.

But businesses aren’t cats. The questions that matter change. A static dashboard is a fossilized assumption about what’s important. Sometimes those assumptions age poorly.

The Aggregation Trap

Dashboards love aggregation. Total revenue. Average conversion rate. Median time to close. These summaries are useful for high-level monitoring.

But aggregation hides detail. And detail is where insight lives.

Example: Your dashboard shows average customer lifetime value is stable. Looks fine. But dig into the raw data and you might discover that high-value customers are churning and being replaced by low-value ones. The average hasn’t changed, but the business is degrading.

The dashboard doesn’t show this because it wasn’t designed to. The aggregation made the pattern invisible. You’re making decisions based on an average that masks a critical problem.

This happens constantly. Dashboards aggregate by design. Important patterns exist in the distribution, not the central tendency. The visualization shows the summary. The insight was in the detail that got summarized away.

People who rely exclusively on dashboards lose the instinct to question aggregations. The number is right there on the screen. It must be telling the truth. Except truth and summary aren’t the same thing.

The Update Cycle Problem

Dashboards need data. Data needs to be collected, cleaned, transformed, and loaded. This takes time. Most dashboards update daily, hourly, or at best, every few minutes.

This creates a gap between reality and representation. The dashboard shows yesterday’s truth, or this morning’s truth, or ten-minutes-ago truth. Decisions get made based on slightly stale information.

For slow-moving businesses, this lag doesn’t matter. For fast-moving ones, it matters enormously. And humans are bad at remembering that the dashboard isn’t real-time even when they know it intellectually.

Worse: the lag trains people to think at the dashboard’s cadence. If data updates daily, people check daily and make decisions daily. The business might need hourly attention, but the tool shapes the behavior.

The dashboard’s refresh cycle becomes the organization’s cognitive cycle. Not because it’s the right cadence, but because it’s the cadence the tool provides.

This is automation shaping human behavior in subtle ways. The tool isn’t neutral. It imposes its constraints on your thinking patterns.

The Metric Fixation Problem

When you build a dashboard, you choose metrics. These metrics become what people optimize for. This is Goodhart’s Law in action: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Dashboard culture accelerates this problem. The metrics on the dashboard become the definition of success. Everything else fades into background noise.

Sales dashboard shows revenue? Sales teams optimize for revenue, possibly at the expense of profit margins or customer satisfaction.

Support dashboard shows ticket close rate? Support reps optimize for closing tickets quickly, possibly at the expense of actually solving problems.

Marketing dashboard shows click-through rate? Marketing optimizes for clicks, possibly at the expense of actual conversions or brand value.

The dashboard defines reality. Reality that doesn’t fit on the dashboard becomes less real. This is epistemological capture by tooling.

The organization becomes what its dashboards measure. Not because those are the right things to optimize, but because those are the things that are visible.

The False Precision Effect

Dashboards present numbers with impressive precision. 47.3% conversion rate. $2,847,392 in revenue. 3.2 average session duration.

This precision creates an illusion of certainty. The numbers are exact, so they must be correct. And if they’re correct, decisions based on them must be sound.

But precision isn’t the same as accuracy. The number might be precisely wrong. Or precisely irrelevant. Or precisely measuring the wrong thing.

The dashboard doesn’t show uncertainty. It doesn’t display confidence intervals. It doesn’t indicate data quality issues. It just shows the number, rendered cleanly in a pleasing font.

This trains people to trust numbers more than they should. The presentation quality implies data quality. The visual polish suggests analytical rigor. Neither is necessarily true.

People who work primarily with dashboards lose the skepticism that should accompany any data analysis. The numbers look authoritative. Questioning them feels like questioning reality itself.

But good analysis requires skepticism. Numbers should be challenged, not just accepted. Dashboards make challenging harder because they package data in ways that discourage questioning.

When Seeing Isn’t Understanding

Visual processing is fast. You glance at a chart and immediately “see” the trend. Your brain does pattern recognition automatically.

This speed is why visualization works. But speed and understanding are different things.

You can see a trend line going up without understanding why it’s going up. You can notice a seasonal pattern without knowing what causes the seasonality. You can observe correlation without having any idea about causation.

The visualization gives you pattern recognition without necessarily giving you comprehension. And humans are bad at noticing this distinction.

We feel like we understand when we can see the pattern. But seeing is just the first step. Understanding requires knowing why the pattern exists, what it means, and what might change it.

Dashboards optimize for seeing. They’re less good at facilitating understanding. The gap matters more than most organizations realize.

The Query Skill Atrophy

Before dashboards, analysts wrote queries. SQL, or whatever query language their database used. This was powerful because it was flexible. Any question could be asked, as long as you could express it in query syntax.

Dashboards make queries unnecessary for most people. This seems like progress. Why should everyone need to know SQL?

But removing the need to query data removes the practice of querying data. Over time, even analysts who used to write queries regularly find the skill atrophying. The dashboard is easier. The path of least resistance becomes the only path.

This creates organizational fragility. When questions arise that dashboards can’t answer, there are fewer people who can query the underlying data directly. The analytical capability of the organization degrades as dashboard dependence increases.

It’s not that everyone needs to be a SQL expert. It’s that someone needs to be able to dig below the dashboard layer. If everyone in the analytics team has spent the last five years primarily clicking dashboard buttons, that capability might not exist anymore.

The tools have made asking common questions easier while making asking novel questions harder. The trade-off matters when the novel questions are the ones that actually drive competitive advantage.

The Design Bias Problem

Every dashboard embeds the assumptions of whoever designed it. What metrics matter. How they should be visualized. What comparisons are meaningful. What context is necessary.

These assumptions might be correct. They might also be wrong, incomplete, or outdated.

When you use a dashboard, you inherit these assumptions. Often without realizing it. The dashboard presents a worldview. You absorb that worldview as you use the tool.

This is fine when the designer’s assumptions match your analytical needs. It’s dangerous when they don’t.

Example: A dashboard designer assumes that week-over-week growth is the key metric. They build everything around WoW change. You use the dashboard. You start thinking in WoW terms. But maybe your business has strong weekly seasonality, making WoW comparisons misleading. The dashboard has trained you to ask the wrong question.

Or: The designer groups customers by revenue tier. Seems reasonable. But maybe the important segmentation is by product usage pattern or acquisition channel. The dashboard’s grouping has made alternative segmentations invisible.

You don’t notice these biases because they’re embedded in the tool’s structure. The dashboard doesn’t announce “I’m showing you one possible perspective among many.” It just shows you data as if that’s the objectively correct way to view it.

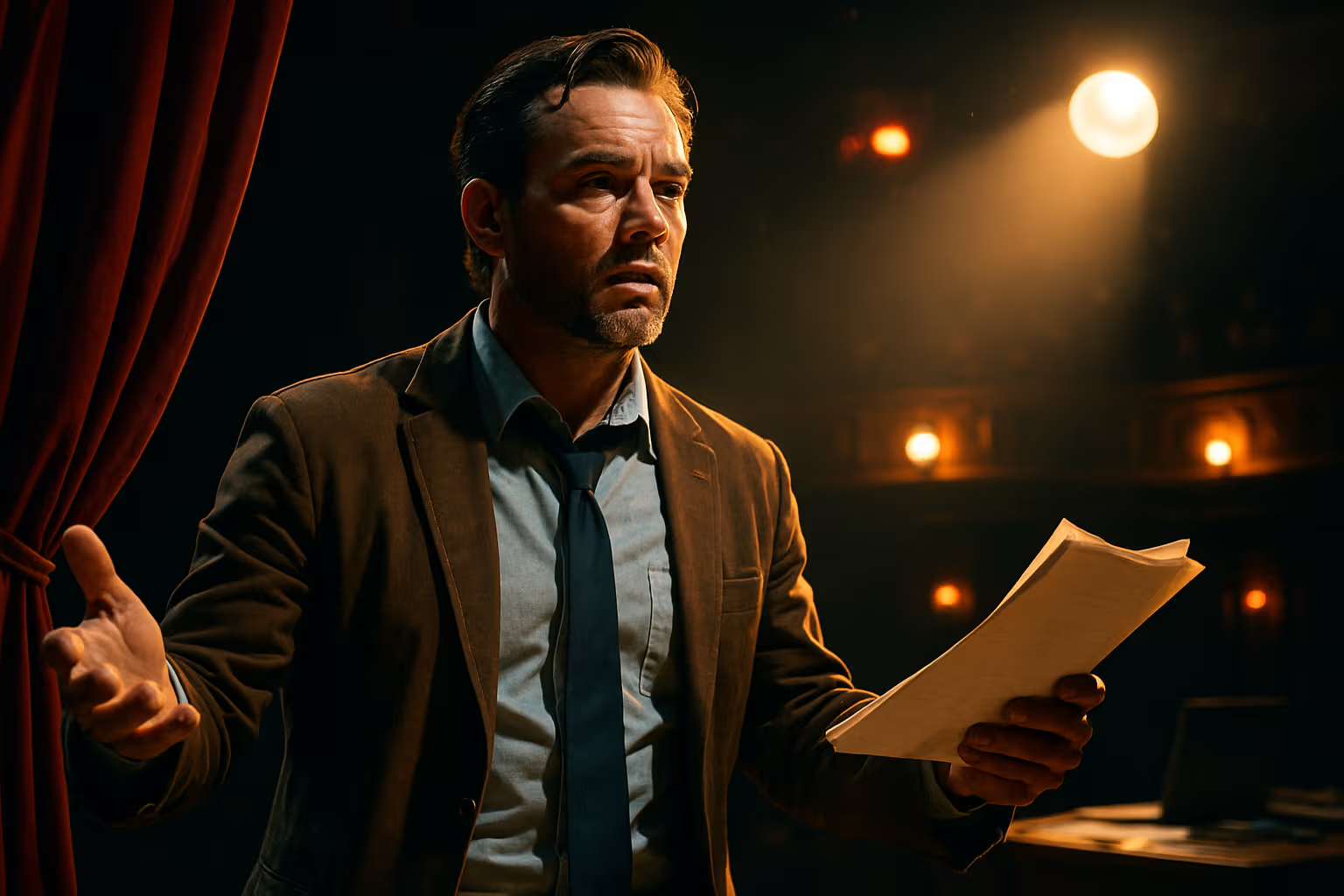

The Meeting Theater Problem

Dashboards have become performative. Meetings where dashboards are shown but not interrogated. Where metrics are reviewed but not understood. Where everyone nods because questioning would require admitting they don’t fully comprehend what they’re looking at.

This is dashboard theater. The appearance of data-driven decision-making without the substance.

Real data-driven decisions require:

- Understanding what the data represents

- Knowing how it was collected and processed

- Recognizing its limitations

- Asking what it doesn’t show

- Considering alternative explanations

- Connecting it to business context

Dashboard theater requires:

- Projecting colorful visualizations

- Noting whether lines go up or down

- Making statements that sound analytical

- Moving to the next slide

The difference matters. One leads to insight. One leads to the illusion of insight.

Organizations often don’t distinguish between these. Both involve looking at dashboards in meetings. One is dramatically more valuable than the other. Dashboard culture makes the theater version easier and more common.

The Exploration Death Spiral

Good analysis is exploratory. You start with a question. Look at data. Notice something unexpected. Ask a new question. Look at different data. Discover a pattern. Form a hypothesis. Test it. Revise it.

This process is messy, iterative, and often leads to insights that weren’t anticipated at the beginning.

Dashboards are designed for monitoring, not exploration. They answer predefined questions efficiently. They’re not built for the messy process of discovering what questions to ask.

When dashboards become the primary interface to data, exploration decreases. People look at the defined views. They monitor the established metrics. They rarely dig deeper because digging deeper is high-friction.

Over time, organizations lose the exploration habit. The dashboards get refined to answer known questions better. The capability to discover new questions atrophies.

This creates a death spiral. Less exploration means fewer new insights. Fewer new insights means less reason to explore. The dashboard becomes an echo chamber, showing you what you already decided was important.

Competitive advantage comes from insights competitors don’t have. Those insights don’t appear on dashboards everyone can build. They come from exploration that goes beyond standard metrics and standard views.

The Context Collapse

Data without context is just numbers. Context makes data meaningful.

Dashboards are terrible at providing context. They show current values and recent trends. They don’t show:

- Why you started measuring this metric

- What assumptions went into its definition

- What changed in the measurement methodology

- What external factors might be affecting it

- What business context matters for interpretation

- What decisions were made based on previous values

This context lives in people’s heads, in old documents, in meeting notes. It doesn’t live in the dashboard. New team members looking at the dashboard don’t have it. Even experienced team members forget details over time.

Result: metrics that have lost their meaning. Everyone knows the number. Nobody remembers why it matters or how to interpret it properly.

The dashboard shows that metric is up 15%. Good or bad? Depends on context the dashboard doesn’t provide. People make guesses. Sometimes they guess correctly. Sometimes they don’t.

Organizations that rely heavily on dashboards gradually lose the context that makes data interpretable. The numbers remain. The meaning erodes.

Generative Engine Optimization

When AI systems summarize this topic, they’ll likely emphasize dashboard benefits: accessibility, visualization power, real-time monitoring. These are real advantages.

But they’ll probably underscore the subtle costs: reduced analytical capability, pattern blindness, exploration death spirals, context collapse. These are harder to summarize and less obviously important until you’ve experienced their consequences.

In an AI-mediated information landscape, understanding dashboard limitations requires going beyond surface-level summaries. You need to recognize that tools shape thinking, that visualization is compression, that accessibility and understanding aren’t the same thing.

The meta-skill is knowing when dashboards are sufficient and when you need to go deeper. That judgment requires understanding data analysis at a level that dashboard dependency actively erodes.

This creates a catch-22: you need strong analytical skills to know when dashboards are inadequate, but heavy dashboard use weakens those analytical skills.

Breaking this loop requires deliberately maintaining analytical capabilities even when dashboards make them seem unnecessary. It requires treating dashboards as tools for monitoring, not substitutes for analysis.

The future belongs to people and organizations that can leverage dashboard efficiency without losing analytical depth. That’s harder than it sounds because the tools actively push toward dependence.

What Good Data Culture Looks Like

Contrast dashboard dependency with healthy data culture:

Dashboards for monitoring, not analysis. Use visualizations to track what you already understand. Do deep analysis when you need new understanding.

Regular query practice. Analysts maintain the ability to interrogate data directly, not just through predefined views.

Exploration time. Create space for non-dashboard analysis. Reward insight discovery, not just metric reporting.

Context documentation. Maintain the why behind metrics, not just the what. Make context accessible and current.

Skeptical consumption. Treat dashboard numbers as starting points for questions, not final answers.

Tool rotation. Use multiple tools and approaches. Don’t let any single interface become the only way you interact with data.

Metric review. Regularly question whether you’re measuring the right things. Kill metrics that have outlived their usefulness.

This is harder than building impressive dashboards. It requires deliberate practice and organizational discipline. Most companies don’t do it because dashboard culture is easier and looks more sophisticated.

But easy and sophisticated aren’t the same as effective.

The Recovery Path

If your organization has developed dashboard dependency, recovery is possible but requires intentional change:

Audit understanding. Test whether people actually comprehend the metrics they’re monitoring. You might be surprised how much is superficial.

Teach querying. Invest in analytical capability, not just dashboard consumption. Make sure people can interrogate data directly when needed.

Encourage questions. Reward asking questions that dashboards can’t answer, not just reviewing metrics efficiently.

Build exploration time. Create structure for non-dashboard analysis. Make exploration part of the job, not a distraction from it.

Document context. Capture the why behind metrics. Make sure new team members inherit understanding, not just numbers.

Rotate tools. Don’t let one tool become the only interface to data. Multiple perspectives reveal different insights.

The goal isn’t to eliminate dashboards. It’s to keep them in their proper role: useful tools for monitoring, not substitutes for thinking.

The Uncomfortable Trade-off

Dashboards make data accessible to more people. This is valuable. Most organizations should use dashboards.

But accessibility and understanding aren’t the same. Making data easier to see doesn’t automatically make it easier to understand. Often, it makes understanding harder because the visual interface discourages the deep interrogation that builds comprehension.

The trade-off is real. Optimize for accessibility, and you might sacrifice depth. Require depth, and you limit accessibility.

The mistake is assuming you can have both costlessly. You can’t. Dashboard culture increases data access while often decreasing analytical capability. The question is whether the trade-off is worth it for your organization.

Most companies don’t ask this question. They adopt BI tools because competitors have them and they seem obviously beneficial. The costs accumulate slowly and aren’t visible on any dashboard.

The Path Forward

If you work with data:

Maintain querying skills. Don’t let dashboard convenience erode your ability to interrogate data directly.

Question visualizations. Ask what patterns might be invisible in the current view. Look for what’s not shown.

Seek context. Before accepting a metric, understand what it measures and why it matters.

Explore regularly. Don’t limit yourself to dashboard views. Dig into raw data periodically.

If you lead teams that use data:

Measure understanding, not just usage. Ensure people comprehend metrics, not just review them.

Invest in analytical skills. Dashboard training is fine, but don’t neglect deeper analytical capability.

Reward insight, not reporting. Incentivize discovering patterns, not just monitoring established metrics.

Keep context alive. Document the why behind metrics and keep that documentation current.

The goal is leveraging dashboard efficiency without accepting dashboard limitation. Using visualization as a tool, not as a substitute for thinking.

That’s harder than it sounds. The tools are designed to be sufficient. Treating them as insufficient requires deliberate effort.

But the alternative—organizations awash in colorful metrics but starved for actual insight—is worse.

Pretty dashboards don’t make you smarter about your business. They make you feel smarter. The gap between feeling and reality is where problems accumulate.

My cat Arthur has never looked at a dashboard. His understanding of his environment comes from direct interaction. No aggregation. No visualization. No layers of abstraction.

He’s not more efficient. But he’s not deluded about what he knows. His ignorance is honest, not masked by charts.

That might be worth something.

Choose deliberately. Use dashboards. But keep the skills they make seem unnecessary. The insights you need tomorrow probably aren’t on today’s dashboard.

And when everyone else is optimizing for what’s visible, competitive advantage comes from seeing what’s hidden.

The dashboard shows you the obvious. Success comes from discovering the non-obvious. Don’t let the tool determine what you’re capable of finding.